Planning AsOf Joins

TL;DR: AsOf Joins are a great example of how DuckDB can choose different implementations for an expensive operation.

“I love it when a plan comes together.”

— Hannibal Smith, The A-Team

Introduction

AsOf joins are a very useful kind of operation for temporal analytics. As the name suggests, they are a kind of lookup for when you have a table of values that change over time, and you want to look up the most recent value at another set of times. Put another way, they let you ask “What was the value of the property as of this time?”

DuckDB added AsOf joins about 18 months ago and you can read that post to learn about their semantics.

What's the Plan?

In that earlier post, I explained why we have a custom operator and syntax for AsOf joins when you can implement them in traditional SQL. The superpower of SQL is that it is declarative: you tell us what you want and we figure out an efficient how. By allowing you to say you want an AsOf join, we can think about how to get you results faster!

Still, the AsOf operator has to do a lot of work. Namely:

- Read all the data in the right side (lookup) table

- Partition it on any equality conditions

- Sort it on the inequality condition

- Repeat the process for the left side (probe) table

- Do a merge join on the two tables that only returns the “most recent” value

That's a lot of data movement! Plus, if any of the tables are large, we may end up exceeding memory and spilling to disk, slowing the operation down even further. Still, as we will see, it is much faster than the plain SQL implementation.

This is such a burden, that many databases that support AsOf joins require the right side table to be partitioned and ordered on any keys you might want to join on. That doesn't fit well with DuckDB's “friendly SQL” approach, so (for now) we have to do it every time.

Let's Get Small

It turns out there is a very common case for AsOf where the left table is small. Suppose you have a year's worth of price data, recorded at high granularity (e.g., fractions of a second), but you only want to look up a small number (say 20) values that are the times you actually bought or sold?

The price table could run to hundreds of millions, if not billions of rows, and just sorting that will take a lot of time and memory. Given how expensive that is, one might wonder if there is a way to avoid all that sorting? Happily the answer is yes!

Simple Joins

Suppose we were to swap the sides of the join, build the old left side as a small right side table, and stream the huge table through the left side of the join. We could use the AsOf conditions for the join, and hopefully find a way to throw out the older matches (we only want to keep the latest match). This would use very little memory, and the streaming could be highly parallelized.

There are two streaming physical join operators we could use for this:

- Nested Loop Join – Literally what it sounds like: loop over each left block and the right side table, checking for matches;

- Piecewise Merge Join – A tricky join for one inequality condition that sorts the right side and each left block before merging to find matches;

We can try both of these once we have a way to eliminate the duplicates.

One thing to be aware of, though, is that they are both N^2 algorithms,

so there will be a limit on how big “small” can be.

Grouping

If you have been around databases long enough,

you know that the phrase “eliminate the duplicates” means GROUP BY!

So to eliminate the duplicates, we want to add an aggregation operator onto the output.

The tricky part is that we want to keep only the matched values that have the “largest” times.

Fortunately, DuckDB has a pair of aggregate functions that do just that:

arg_max and

arg_min

(also called max_by and min_by).

That takes care of the fields from the lookup table, but what about the fields from the small table?

Well, those values will all be the same, so we can just use the first aggregate function for them.

Streaming Window

But what should we group on?

One might be tempted to group on the times that are being looked up,

but that could be problematic if there are duplicate lookup times

(only one of the rows would be returned!).

Instead, we need to have a unique identifier for each row being looked up.

The simplest way to do this is to use the

streaming window operator

with the row_number() window function.

We then group on this row number.

Coming Together

This all sounds good, but how does it work in practice?

How big can “small” get?

To answer that I ran a number of benchmarks joining small tables against large ones.

The tables are called prices and times:

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE prices_{prices_size} AS

SELECT

r AS id,

'2021-01-01T00:00:00'::TIMESTAMP +

INTERVAL (random() * 365 * 24 * 60 * 60) SECOND

AS time,

(random() * 100000)::INTEGER AS price,

FROM range({prices_size}) tbl(r);

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE times_{times_size} AS

SELECT

r AS id,

'2021-01-01'::TIMESTAMP +

INTERVAL ((random() * 365 * 24 * 60 * 60)::INTEGER) SECONDS

AS probe

FROM range({times_size}) tbl(r);

I then ran a benchmark query:

SELECT count(*)

FROM (

SELECT

t.probe,

p.price

FROM times_{times_size} t

ASOF JOIN prices_{prices_size} p

ON t.probe >= p.time

) t;

for a matrix of the following values:

- Prices – 100K to 1B rows in steps of 10×;

- Time – 1 to 2048 rows in steps of 2× (until it got too slow);

- Threads – 36, 18 and 9;

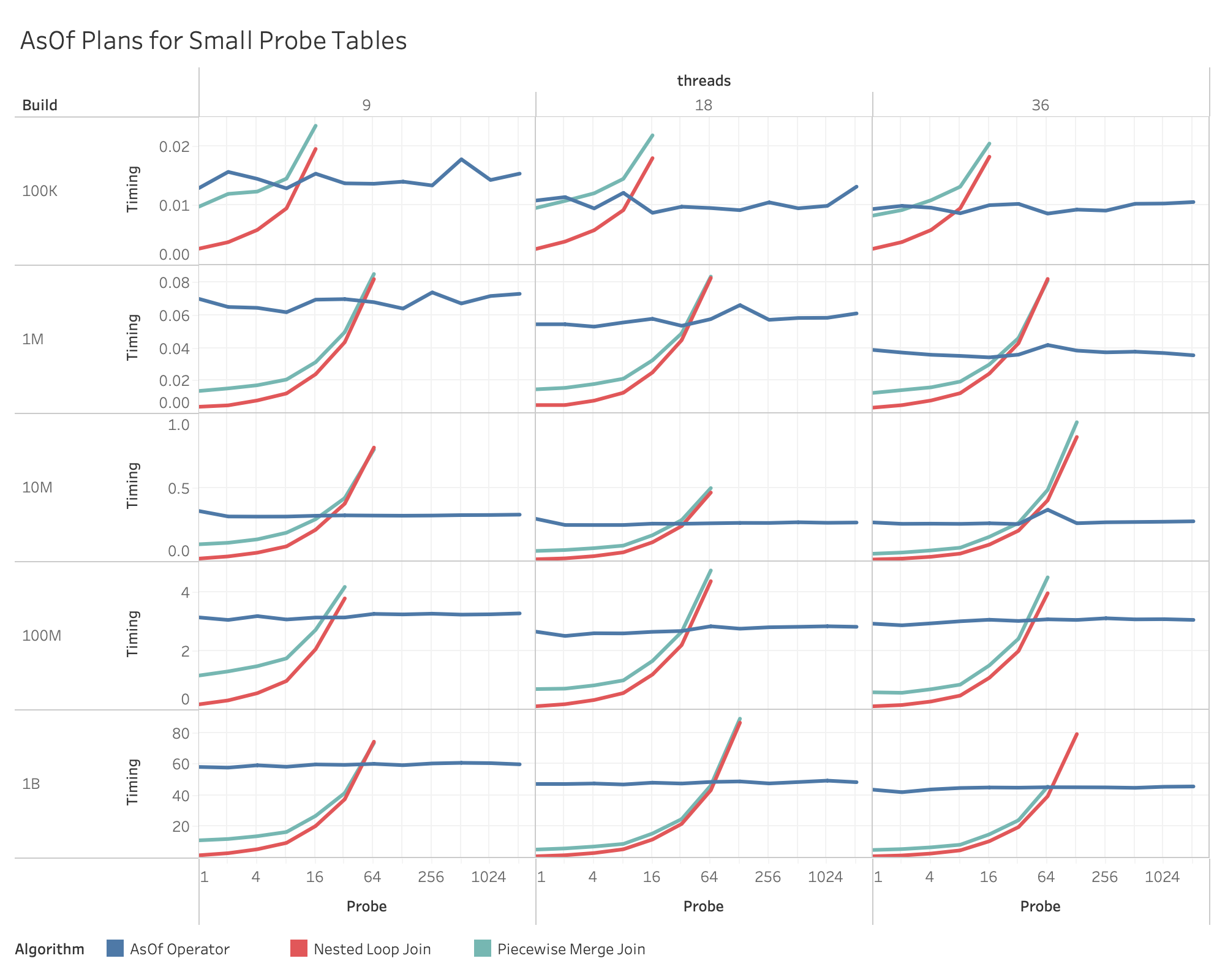

Here are the results:

As you can see, the quadratic nature of the joins means that “small” means “<= 64”. That is pretty small, but the table in the original user issue had only 21 values.

We can also see that the sorting provided by piecewise merge join does not seem to help much, so plain old Nested Loop Join is the best choice.

It is clear that the performance of the standard operator is stable at each size, but decreases slowly as the number of threads increases. This makes sense because sorting is compute-intensive and the fewer cores we can assign, the longer it will take.

If you want to play with the data more, you can find the interactive vizualization on our Tableau Public site.

Memory

The Loop Join plan is clearly faster at small sizes, but how much memory do the two plans use? These are the rough amounts of memory needed before excessive paging or allocation failures occur:

| Price Rows | AsOf Memory | Loop Join Memory |

|---|---|---|

| 1B | 48 GB | 64 MB |

| 100M | 6 GB | 64 MB |

| 10M | 256 MB | 64 MB |

| 1M | 32 MB | 64 MB |

| 100K | 32 MB | 64 MB |

In other words, the Loop Join plan only needs enough memory to page in the lookup table! So if the table is large and you have limited memory, the Loop Join plan is the best option, even if it is painfully slow. Just remember that the Loop Join plan has to compete with the speed of the standard operator under paging, and that may still be faster past a certain point.

Backup Plans

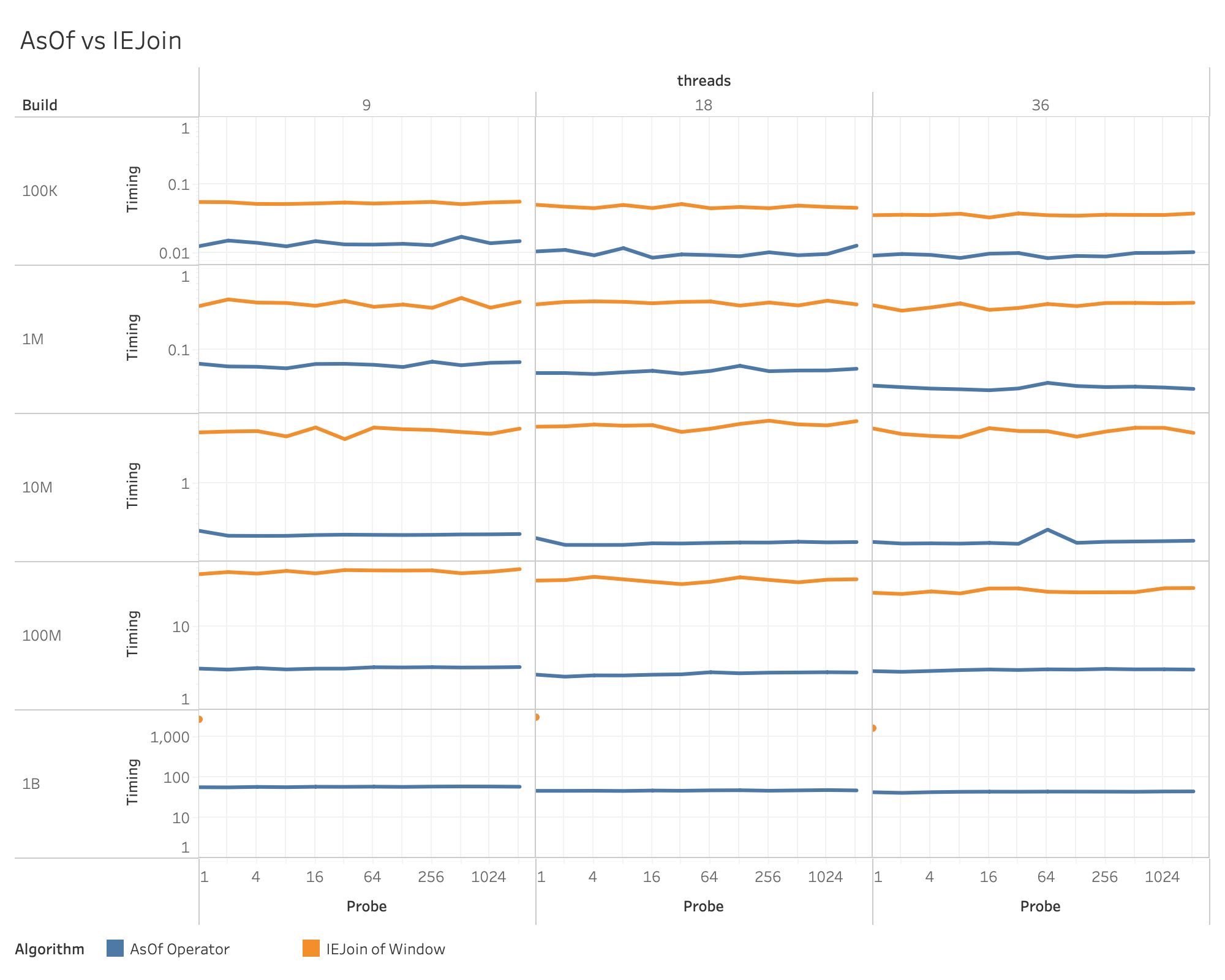

As part of the experiment, I also measured how the old SQL implementation would perform, and it did not fare well. At the 1B row level I had to cut it off after one run to avoid wasting time:

Note that the Y-axis is a log scale here!

Setting

While it is nice that we provide a default value for making plan choices like this, your mileage may vary as they say.

If you have more time than memory, it might be worth it to you to bump up the Loop Join threshold a bit.

The threshold is a new setting called asof_loop_join_threshold with a default value of 64,

and you can change it using a PRAGMA statement:

PRAGMA asof_loop_join_threshold = 128;

Remember, though, this is a quadratic operation, and pushing it up too high might take a Very Long Time (especially if you express it in Old Entish!).

If you wish to disable the feature, you can just set it to zero:

PRAGMA asof_loop_join_threshold = 0;

Roll Your Own

This Loop Join plan optimization will not ship until v1.3, but if you are having problems today, you can always write your own version like this:

SELECT

first(t.probe) AS probe,

arg_max(p.price, p.time) AS price

FROM prices p

INNER JOIN (

SELECT

*,

row_number() OVER () AS pk

FROM times

) t

ON t.probe >= p.time

GROUP BY pk

ORDER BY 1;

If you know the probe times are unique, you can simplify this to:

SELECT

t.probe,

arg_max(p.price, p.time) AS price

FROM prices p

INNER JOIN times t

ON t.probe >= p.time

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1;

Future Work

The new AsOf Loop Join plan feature only covers a common but very specific situation, and the standard operator could be made a lot more efficient if it knew that the data was already sorted. This is often the case, but we do not yet have the ability to track partitioning and ordering between operators. Tracking that kind of metadata would be very useful for speeding up a large number of operations, including sorting (!), partitioned aggregation, windowing, AsOf joins and merge joins. This is work we are very interested in, so stay tuned!

Conclusion

With apologies to Guido van Rossum, there is usually more than one way to do something, but each way may have radically different performance characteristics. One of the jobs of a relational database with a declarative query language like SQL is to make intelligent choices between the options so you the user can focus on the result. Here at DuckDB we look forward to finding more ways to plan your queries so you can focus on what you do best!

Notes

- The tests were all run on an iMac Pro with a 2.3 GHz 18-core Intel Xeon W CPU and 128 GB of RAM.

- The raw test data and visualizations are available on our Tableau Public repository.

- The script to generate the data is in my public DuckDB tools repository.