DuckDB's AsOf Joins: Fuzzy Temporal Lookups

TL;DR: DuckDB supports AsOf Joins – a way to match nearby values. They are especially useful for searching event tables for temporal analytics.

Do you have time series data that you want to join, but the timestamps don't quite match? Or do you want to look up a value that changes over time using the times in another table? And did you end up writing convoluted (and slow) inequality joins to get your results? Then this post is for you!

What Is an AsOf Join?

Time series data is not always perfectly aligned. Clocks may be slightly off, or there may be a delay between cause and effect. This can make connecting two sets of ordered data challenging. AsOf Joins are a tool for solving this and other similar problems.

One of the problems that AsOf Joins are used to solve is finding the value of a varying property at a specific point in time. This use case is so common that it is where the name came from: Give me the value of the property as of this time.

More generally, however, AsOf joins embody some common temporal analytic semantics, which can be cumbersome and slow to implement in standard SQL.

Portfolio Example

Let's start with a concrete example.

Suppose we have a table of stock prices with timestamps:

| ticker | when | price |

|---|---|---|

| APPL | 2001-01-01 00:00:00 | 1 |

| APPL | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 | 2 |

| APPL | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 | 3 |

| MSFT | 2001-01-01 00:00:00 | 1 |

| MSFT | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 | 2 |

| MSFT | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 | 3 |

| GOOG | 2001-01-01 00:00:00 | 1 |

| GOOG | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 | 2 |

| GOOG | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 | 3 |

We have another table containing portfolio holdings at various points in time:

| ticker | when | shares |

|---|---|---|

| APPL | 2000-12-31 23:59:30 | 5.16 |

| APPL | 2001-01-01 00:00:30 | 2.94 |

| APPL | 2001-01-01 00:01:30 | 24.13 |

| GOOG | 2000-12-31 23:59:30 | 9.33 |

| GOOG | 2001-01-01 00:00:30 | 23.45 |

| GOOG | 2001-01-01 00:01:30 | 10.58 |

| DATA | 2000-12-31 23:59:30 | 6.65 |

| DATA | 2001-01-01 00:00:30 | 17.95 |

| DATA | 2001-01-01 00:01:30 | 18.37 |

We can compute the value of each holding at that point in time by finding the most recent price before the holding's timestamp by using an AsOf Join:

SELECT h.ticker, h.when, price * shares AS value

FROM holdings h ASOF JOIN prices p

ON h.ticker = p.ticker

AND h.when >= p.when;

This attaches the value of the holding at that time to each row:

| ticker | when | value |

|---|---|---|

| APPL | 2001-01-01 00:00:30 | 2.94 |

| APPL | 2001-01-01 00:01:30 | 48.26 |

| GOOG | 2001-01-01 00:00:30 | 23.45 |

| GOOG | 2001-01-01 00:01:30 | 21.16 |

It essentially executes a function defined by looking up nearby values in the prices table.

Note also that missing ticker values do not have a match and don't appear in the output.

Outer AsOf Joins

Because AsOf produces at most one match from the right hand side, the left side table will not grow as a result of the join, but it could shrink if there are missing times on the right. To handle this situation, you can use an outer AsOf Join:

SELECT h.ticker, h.when, price * shares AS value

FROM holdings h ASOF LEFT JOIN prices p

ON h.ticker = p.ticker

AND h.when >= p.when

ORDER BY ALL;

As you might expect, this will produce NULL prices and values instead of dropping left side rows

when there is no ticker or the time is before the prices begin.

| ticker | when | value |

|---|---|---|

| APPL | 2000-12-31 23:59:30 | |

| APPL | 2001-01-01 00:00:30 | 2.94 |

| APPL | 2001-01-01 00:01:30 | 48.26 |

| GOOG | 2000-12-31 23:59:30 | |

| GOOG | 2001-01-01 00:00:30 | 23.45 |

| GOOG | 2001-01-01 00:01:30 | 21.16 |

| DATA | 2000-12-31 23:59:30 | |

| DATA | 2001-01-01 00:00:30 | |

| DATA | 2001-01-01 00:01:30 |

Windowing Alternative

Standard SQL can implement this kind of join, but you need to use a window function and an inequality join. These can both be fairly expensive operations, but the query would look like this:

WITH state AS (

SELECT

ticker,

price,

"when",

lead("when", 1, 'infinity')

OVER (PARTITION BY ticker ORDER BY "when") AS end

FROM prices

)

SELECT h.ticker, h.when, price * shares AS value

FROM holdings h

INNER JOIN state s

ON h.ticker = s.ticker

AND h.when >= s.when

AND h.when < s.end;

The default value of infinity is used to make sure there is an end value for the last row that can be compared.

Here is what the state CTE looks like for our example:

| ticker | price | when | end |

|---|---|---|---|

| APPL | 1 | 2001-01-01 00:00:00 | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 |

| APPL | 2 | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 |

| APPL | 3 | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 | infinity |

| GOOG | 1 | 2001-01-01 00:00:00 | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 |

| GOOG | 2 | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 |

| GOOG | 3 | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 | infinity |

| MSFT | 1 | 2001-01-01 00:00:00 | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 |

| MSFT | 2 | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 |

| MSFT | 3 | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 | infinity |

In the case where there is no equality condition, the planner would have to use an inequality join,

which can be very expensive.

And even in the equality condition case,

the resulting hash join may end up with long chains of identical ticker keys that will all match and need pruning.

Why AsOf?

If SQL can compute AsOf joins already, why do we need a new join type? There are two big reasons: expressibility and performance. The windowing alternative is more verbose and harder to understand than the AsOf syntax, so making it easier to say what you are doing helps others (or even you!) understand what is happening.

The syntax also makes it easier for DuckDB to understand what you want and produce your results faster. The window and inequality join version loses the valuable information that the intervals do not overlap. It also prevents the query optimizer from moving the join because SQL insists that windowing happens after joins. By treating the operation as a join with known data constraints, DuckDB can move the join for performance and use a tailored join algorithm. The algorithm we use is to sort the right side table and then do a kind of merge join with the left side values. But unlike a standard merge join, AsOf can stop searching when it finds the first match because there is at most one match.

State Tables

You may be wondering why the Common Table Expression in the WITH clause was called state.

This is because the prices table is really an example of what in temporal analytics is called an event table .

The rows of an event table contain timestamps and what happened at that time (i.e., events).

The events in the prices table are changes to the price of a stock.

Another common example of an event table is a structured log file:

Each row of the log records when something "happened" – usually a change to a part of the system.

Event tables are difficult to work with because each fact only has the start time. In order to know whether the fact is still true (or true at a specific time) you need the end time as well. A table with both the start and end time is called a state table. Converting event tables to state tables is a common temporal data preparation task, and the windowing CTE above shows how to do it in general using SQL.

Sentinel Values

One limitation of the windowing approach is that

the ordering type needs to have sentinel value that can be used if it does not support infinity,

either an unused value or NULL.

Both of these choices are potentially problematic.

In the first case, it may not be easy to determine an upper sentinel value

(suppose the ordering was a string column?)

In the second case, you would need to write the condition as

h.when < s.end OR s.end IS NULL

and using an OR like this in a join condition makes comparisons slow and hard to optimize.

Moreover, if the ordering column is already using NULL to indicate missing values,

this option is not available.

For most state tables, there are suitable choices (e.g., large dates) but one of the advantages of AsOf is that it can avoid having to design a state table if it is not needed for the analytic task.

Event Table Variants

So far we have been using a standard type of event table where the timestamps are assumed to be the start of the state transitions. But AsOf can now use any inequality, which allows it to handle other types of event tables.

To explore this, let's use two very simple tables with no equality conditions. The build side will just have four integer "timestamps" with alphabetic values:

| Time | Value |

|---|---|

| 1 | a |

| 2 | b |

| 3 | c |

| 4 | d |

The probe table will just be the time values plus the midpoints, and we can make a table showing what value each probe time matches for greater than or equal to:

| Probe | >= |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | |

| 1.0 | a |

| 1.5 | a |

| 2.0 | b |

| 2.5 | b |

| 3.0 | c |

| 3.5 | c |

| 4.0 | d |

| 4.5 | d |

This shows us that the interval a probe value matches is in the half-open interval [Tn, Tn+1).

Now let's see what happens if use strictly greater than as the inequality:

| Probe | > |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | |

| 1.0 | |

| 1.5 | a |

| 2.0 | a |

| 2.5 | b |

| 3.0 | b |

| 3.5 | c |

| 4.0 | c |

| 4.5 | d |

Now we can see that the interval a probe value matches is in the half-open interval (Tn, Tn+1].

The only difference is that the interval is closed at the end instead of the beginning.

This means that for this inequality type, the time is not part of the interval.

What if the inequality goes in the other direction, say less than or equal to?

| Probe | <= |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | a |

| 1.0 | a |

| 1.5 | b |

| 2.0 | b |

| 2.5 | c |

| 3.0 | c |

| 3.5 | d |

| 4.0 | d |

| 4.5 |

Again, we have half-open intervals, but this time we are matching the previous interval (Tn-1, Tn].

One way to interpret this is that the times in the build table are the end of the interval,

instead of the beginning.

Also, unlike greater than or equal to,

the interval is closed at the end instead of the beginning.

Adding this to what we found for strictly greater than,

we can interpret this as meaning that the lookup times are part of the interval

when non-strict inequalities are used.

We can check this by looking at the last inequality: strictly less than:

| Probe | < |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | a |

| 1.0 | b |

| 1.5 | b |

| 2.0 | c |

| 2.5 | c |

| 3.0 | d |

| 3.5 | d |

| 4.0 | |

| 4.5 |

In this case the matching intervals are [Tn-1, Tn).

This is a strict inequality, so the table time is not in the interval,

and it is a less than, so the time is the end of the interval.

To sum up, here is the full list:

| Inequality | Interval |

|---|---|

| > | (Tn, Tn+1] |

| >= | [Tn, Tn+1) |

| <= | (Tn-1, Tn] |

| < | [Tn-1, Tn) |

We now have two natural interpretations of what the inequalities mean:

- The greater (resp. less) than inequalities mean the time is the beginning (resp. end) of the interval.

- The strict (resp. non-strict) inequalities mean the time is excluded from (resp. included in) the interval.

So if we know whether the time marks the start or the end of the event, and whether the time is include or excluded, we can choose the appropriate AsOf inequality.

Usage

So far we have been explicit about specifying the conditions for AsOf,

but SQL also has a simplified join condition syntax

for the common case where the column names are the same in both tables.

This syntax uses the USING keyword to list the fields that should be compared for equality.

AsOf also supports this syntax, but with two restrictions:

- The last field is the inequality

- The inequality is

>=(the most common case)

Our first query can then be written as:

SELECT ticker, h.when, price * shares AS value

FROM holdings h

ASOF JOIN prices p

USING(ticker, "when");

Be aware that if you don't explicitly list the columns in the SELECT,

the ordering field value will be the probe value, not the build value.

For a natural join, this is not an issue because all the conditions are equalities,

but for AsOf, one side has to be chosen.

Since AsOf can be viewed as a lookup function,

it is more natural to return the "function arguments" than the function internals.

Under the Hood

What an AsOf Join is really doing is allowing you to treat an event table as a state table for join operations. By knowing the semantics of the join, it can avoid creating a full state table and be more efficient than a general inequality join.

Let's start by looking at how the windowing version works. Remember that we used this query to convert the event table to a state table:

WITH state AS (

SELECT

ticker,

price,

"when",

lead("when", 1, 'infinity')

OVER (PARTITION BY ticker ORDER BY "when") AS end

FROM prices

);

The state table CTE is created by hash partitioning the table on ticker,

sorting on when and then computing another column that is just when shifted down by one.

The join is then implemented with a hash join on ticker and two comparisons on when.

If there was no ticker column (e.g., the prices were for a single item)

then the join would be implemented using our inequality join operator,

which would materialise and sort both sides because it doesn't know that the ranges are disjoint.

The AsOf operator uses all three operator pipeline APIs to consolidate and collect rows.

During the sink phase, AsOf hash partitions and sorts the right hand side to make a temporary state table.

(In fact it uses the same code as Window,

but without unnecessarily materialising the end column.)

During the operator phase, it filters out (or returns) rows that cannot match

because of NULL values in the predicate expressions,

and then hash partitions and sorts the remaining rows into a cache.

Finally, during the source phase, it matches hash partitions

and then merge joins the sorted values within each hash partition.

Benchmarks

Because AsOf joins can be implemented in various ways using standard SQL queries, benchmarking is really about comparing the various alternatives.

One alternative is a debugging PRAGMA for AsOf called debug_asof_iejoin,

which implements the join using Window and IEJoin.

This allows us to easily toggle between the implementations and compare runtimes.

Other alternatives combine equi-joins and window functions. The equi-join is used to implement the equality matching conditions, and the window is used to select the closest inequality. We will now look at two different windowing techniques and compare their performance. If you wish to skip this section, the bottom line is that while they are sometimes a bit faster, the AsOf join has the most consistent behavior of all the algorithms.

Window as State Table

The first benchmark compares a hash join with a state table. It probes a 5M row table of values built from 100K timestamps and 50 partitioning keys using a self-join where only 50% of the keys are present and the timestamps have been shifted to be halfway between the originals:

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE build AS (

SELECT k, '2001-01-01 00:00:00'::TIMESTAMP + INTERVAL (v) MINUTE AS t, v

FROM range(0, 100_000) vals(v), range(0, 50) keys(k)

);

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE probe AS (

SELECT k * 2 AS k, t - INTERVAL (30) SECOND AS t

FROM build

);

The build table looks like this:

| k | t | v |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2001-01-01 00:00:00 | 0 |

| 0 | 2001-01-01 00:01:00 | 1 |

| 0 | 2001-01-01 00:02:00 | 2 |

| 0 | 2001-01-01 00:03:00 | 3 |

| … | … | … |

and the probe table looks like this (with only even values for k):

| k | t |

|---|---|

| 0 | 2000-12-31 23:59:30 |

| 0 | 2001-01-01 00:00:30 |

| 0 | 2001-01-01 00:01:30 |

| 0 | 2001-01-01 00:02:30 |

| 0 | 2001-01-01 00:03:30 |

| … | … |

The benchmark just does the join and sums up the v column:

SELECT sum(v)

FROM probe

ASOF JOIN build USING(k, t);

The debugging PRAGMA does not allow us to use a hash join,

but we can create the state table in a CTE again and use an inner join:

-- Hash Join implementation

WITH state AS (

SELECT k,

t AS begin,

v,

lead(t, 1, 'infinity'::TIMESTAMP) OVER (PARTITION BY k ORDER BY t) AS end

FROM build

)

SELECT sum(v)

FROM probe p

INNER JOIN state s

ON p.t >= s.begin

AND p.t < s.end

AND p.k = s.k;

This works because the planner assumes that equality conditions are more selective than inequalities and generates a hash join with a filter.

Running the benchmark, we get results like this:

| Algorithm | Median of 5 |

|---|---|

| AsOf | 0.425 s |

| IEJoin | 3.522 s |

| State Join | 192.460 s |

The runtime improvement of AsOf over IEJoin here is about 9×. The horrible performance of the Hash Join is caused by the long (100K) bucket chains in the hash table.

The second benchmark tests the case where the probe side is about 10× smaller than the build side:

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE probe AS

SELECT k,

'2021-01-01T00:00:00'::TIMESTAMP +

INTERVAL (random() * 60 * 60 * 24 * 365) SECOND AS t,

FROM range(0, 100_000) tbl(k);

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE build AS

SELECT r % 100_000 AS k,

'2021-01-01T00:00:00'::TIMESTAMP +

INTERVAL (random() * 60 * 60 * 24 * 365) SECOND AS t,

(random() * 100_000)::INTEGER AS v

FROM range(0, 1_000_000) tbl(r);

SELECT sum(v)

FROM probe p

ASOF JOIN build b

ON p.k = b.k

AND p.t >= b.t

-- Hash Join Version

WITH state AS (

SELECT k,

t AS begin,

v,

lead(t, 1, 'infinity'::TIMESTAMP)

OVER (PARTITION BY k ORDER BY t) AS end

FROM build

)

SELECT sum(v)

FROM probe p

INNER JOIN state s

ON p.t >= s.begin

AND p.t < s.end

AND p.k = s.k;

| Algorithm | Median of 5 runs |

|---|---|

| State Join | 0.065 s |

| AsOf | 0.077 s |

| IEJoin | 49.508 s |

Now the runtime improvement of AsOf over IEJoin is huge (~500×) because it can leverage the partitioning to eliminate almost all of the equality mismatches.

The Hash Join implementation does much better here because the optimizer notices that the probe side is smaller and builds the hash table on the "probe" table. Also, the probe values here are unique, so the hash table chains are minimal.

Window with Ranking

Another way to use the window operator is to:

- Join the tables on the equality predicates

- Filter to pairs where the build time is before the probe time

- Partition the result on both the equality keys and the probe timestamp

- Sort the partitions on the build timestamp descending

- Filter out all value except rank 1 (i.e., the largest build time <= the probe time)

The query looks like:

WITH win AS (

SELECT p.k, p.t, v,

rank() OVER (PARTITION BY p.k, p.t ORDER BY b.t DESC) AS r

FROM probe p INNER JOIN build b

ON p.k = b.k

AND p.t >= b.t

QUALIFY r = 1

)

SELECT k, t, v

FROM win;

The advantage of this windowing query is that it does not require sentinel values, so it can work with any data type. The disadvantage is that it creates many more partitions because it includes both timestamps, which requires more complex sorting. Moreover, because it applies the window after the join, it can produce huge intermediates that can result in external sorting and expensive out-of-memory operations.

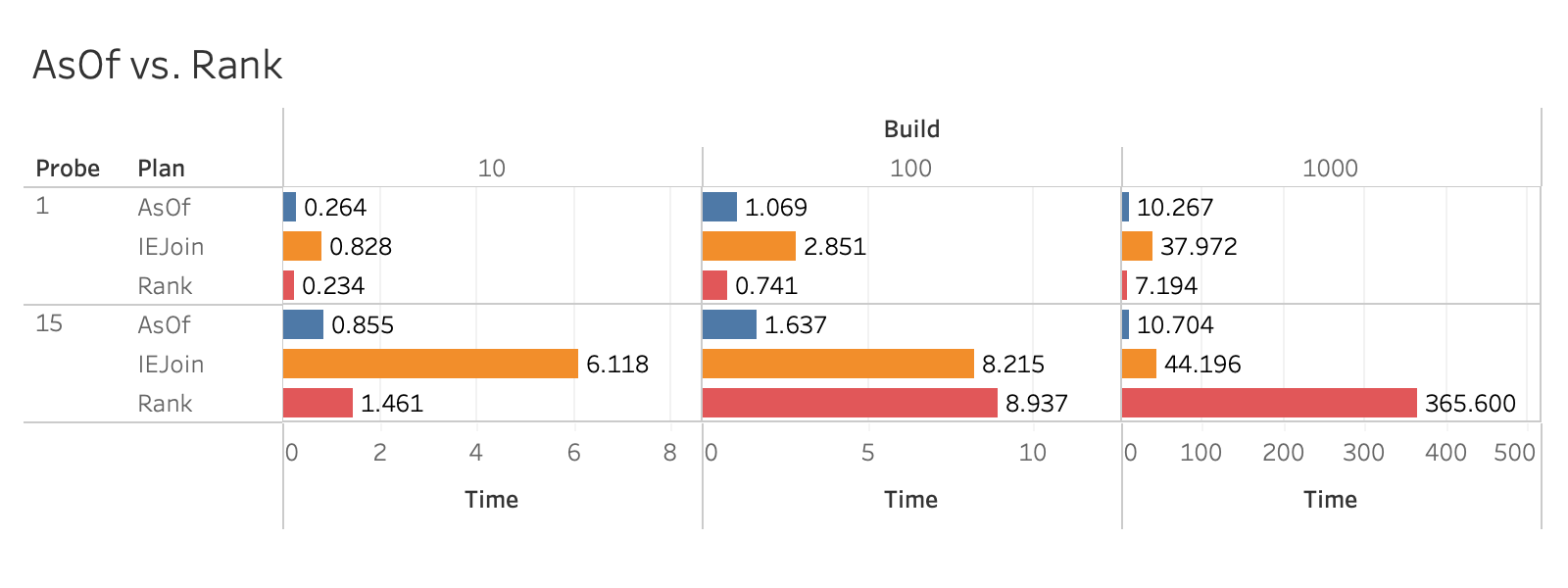

For this benchmark, we will be using three build tables, and two probe tables, all containing 10K integer equality keys. The probe tables have either 1 or 15 timestamps per key:

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE probe15 AS

SELECT k, t

FROM range(10_000) cs(k),

range('2022-01-01'::TIMESTAMP, '2023-01-01'::TIMESTAMP, INTERVAL 26 DAY) ts(t);

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE probe1 AS

SELECT k, '2022-01-01'::TIMESTAMP t

FROM range(10_000) cs(k);

The build tables are much larger and have approximately 10/100/1000× the number of entries as the 15 element tables:

-- 10:1

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE build10 AS

SELECT k, t, (random() * 1000)::DECIMAL(7, 2) AS v

FROM range(10_000) ks(k),

range('2022-01-01'::TIMESTAMP, '2023-01-01'::TIMESTAMP, INTERVAL 59 HOUR) ts(t);

-- 100:1

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE build100 AS

SELECT k, t, (random() * 1000)::DECIMAL(7, 2) AS v

FROM range(10_000) ks(k),

range('2022-01-01'::TIMESTAMP, '2023-01-01'::TIMESTAMP, INTERVAL 350 MINUTE) ts(t);

-- 1000:1

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE build1000 AS

SELECT k, t, (random() * 1000)::DECIMAL(7, 2) AS v

FROM range(10_000) ks(k),

range('2022-01-01'::TIMESTAMP, '2023-01-01'::TIMESTAMP, INTERVAL 35 MINUTE) ts(t);

The AsOf join queries are:

-- AsOf/IEJoin

SELECT p.k, p.t, v

FROM probe p ASOF JOIN build b

ON p.k = b.k

AND p.t >= b.t

ORDER BY 1, 2;

-- Rank

WITH win AS (

SELECT p.k, p.t, v,

rank() OVER (PARTITION BY p.k, p.t ORDER BY b.t DESC) AS r

FROM probe p INNER JOIN build b

ON p.k = b.k

AND p.t >= b.t

QUALIFY r = 1

)

SELECT k, t, v

FROM win

ORDER BY 1, 2;

The results are shown here:

(Median of 5 except for Rank/15/1000).

- For all ratios with 15 probes, AsOf is the most performant.

- For small ratios with 15 probes, Rank beats IEJoin (both with windowing), but by 100:1 it is starting to explode.

- For single element probes, Rank is most effective, but even there, its edge over AsOf is only about 50% at scale.

This shows that AsOf could be possibly be improved upon, but predicting where that happens would be tricky, and getting it wrong would have enormous costs.

Future Work

DuckDB can now execute AsOf joins for all inequality types with reasonable performance. In some cases, the performance gain is several orders of magnitude over the standard SQL versions – even with our fast inequality join operator.

While the current AsOf operator is completely general, there are a couple of planning optimisations that could be applied here.

- When there are selective equality conditions, it is likely that a hash join with filtering against a materialised state table would be significantly faster. If we can detect this and suitable sentinel values are available, the planner could choose to use a hash join instead of the default AsOf implementation.

- There are also use cases where the probe table is much smaller than the build table, along with equality conditions, and performing a hash join against the probe table could yield significant performance improvements.

Nevertheless, remember that one of the advantages of SQL is that it is a declarative language:

You specify what you want and leave it up to the database to figure out how.

Now that we have defined the semantics of the AsOf join,

you the user can write queries saying this is what you want – and we are free to keep improving the how!

Happy Joining!

One of the most interesting parts of working on DuckDB is that it stretches the traditional SQL model of unordered data. DuckDB makes it easy to query ordered data sets such as data frames and Parquet files, and when you have data like that, you expect to be able to do ordered analysis! Implementing Fast Sorting, Fast Windowing and Fast AsOf joins is how we are making this expectation a reality.