Analytics-Optimized Concurrent Transactions

TL;DR: DuckDB employs unique analytics-optimized optimistic multi-version concurrency control techniques. These allow DuckDB to perform large-scale in-place updates efficiently.

This is the second post on DuckDB's ACID support. If you have not read the first post, Changing Data with Confidence and ACID, it may be a good idea to start there.

In our previous post, we have discussed why changes to data are much saner if the formal “ACID” transaction properties hold. A data system should not allow importing “half” a CSV file into a table because of some unexpected string in line 431,741.

Ensuring the ACID properties of transactions under concurrency is very challenging and one of the “holy grails” of databases. DuckDB implements advanced methods for concurrency control and logging. In this post, we describe DuckDB's Multi-Version Concurrency (MVCC) and Write-Ahead-Logging (WAL) schemes that are specifically designed for efficiently ensuring the transactional guarantees for analytical use cases under concurrent workloads.

Concurrency Control

Pessimistic Concurrency Control. Traditional database systems use locks to manage concurrency. A transaction obtains locks in order to ensure that (a) no other transaction can see its uncommitted changes, and (b) it does not see uncommitted changes of other transactions. Locks need to be obtained both when reading (shared locks) and when writing (exclusive locks). When a different transaction tries to read data that has been written to by another transaction – it must wait for the other transaction to complete and release its exclusive lock on the data. This type of concurrency control is called pessimistic, because locks are always obtained, even if there are no conflicts between transactions.

This strategy works well for transactional workloads. These workloads consist of small transactions that read or modify a few rows. A typical transaction only locks a few rows, and keeps those rows locked only for a short period of time. For analytical workloads, on the other hand, this strategy does not work well. These workloads consist of large transactions that read or modify large parts of the table. An analytical transaction executed in a system that uses pessimistic concurrency control will therefore lock many rows, and keep those rows locked for a long period of time, preventing other transactions from executing.

Optimistic Concurrency Control. DuckDB uses a different approach to manage concurrency conflicts. Transactions do not hold locks – they can always read and write to any row in any table. When a conflict occurs and multiple transactions try to write to the same row at the same time – one of the conflicting transactions is instead aborted. The aborted transaction can then be retried if desired. This type of concurrency control is called optimistic.

In case there are never any concurrency conflicts – this strategy is very efficient as we have not unnecessarily slowed down transactions by pessimistically grabbing locks. This strategy works well for analytical workloads – as read-only transactions can never conflict with one another, and multiple writers that modify the same rows are rare in these workloads.

Multi-Version Concurrency Control

In an optimistic concurrency control model – multiple transactions can read and make changes to the same tables at the same time. We have to ensure these transactions cannot see each others' half-done changes in order to maintain ACID isolation. A well-known technique to achieve this is Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC). MVCC works by keeping multiple versions of modified rows. When a transaction modifies a row – we can create a copy of that row and modify that instead. This allows other transactions to keep on reading the original version of the row. This allows for each transaction to see their own, consistent state of the database. Often that state is the "version" that existed when the transaction was started. MVCC is widely used in database systems, for example PostgreSQL also uses MVCC.

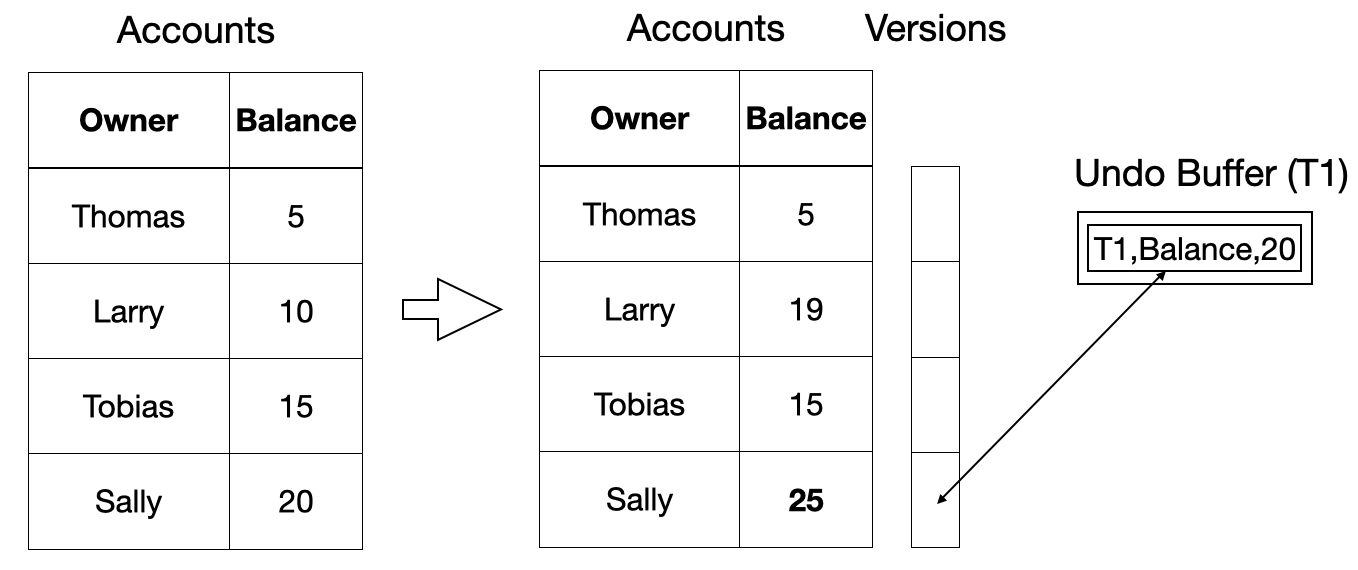

DuckDB implements MVCC using a technique inspired by the paper “Fast Serializable Multi-Version Concurrency Control for Main-Memory Database Systems” by the one and only Thomas Neumann. This MVCC implementation works by maintaining a list of previous versions to each row in a table. Transactions will update the table data in-place, but will save the previous version of the updated row in the undo buffers. Below is an illustrated example.

-- add 5 to Sally's balance

UPDATE Accounts SET Balance = Balance + 5 WHERE Name = 'Sally';

When reading a row, a transaction will first check if there is version information for that row. If there is none, which is the common case, the transaction can read the original data. If there is version information, the transaction has to compare the transaction number at the transaction's start time with those in the undo buffers and pick the right version to read.

Efficient MVCC for Analytics

The above approach works well for transactional workloads where individual rows are changed frequently. For analytical use cases, we observe a very different usage pattern: changes are much more “bulky” and they often only affect a subset of columns. For example, we do not usually delete individual rows but instead delete all rows matching a pattern, e.g.:

DELETE FROM orders WHERE order_time < DATE '2010-01-01';

We also commonly bulk update columns, e.g., to fix the evergreen annoyance of people using nonsensical in-domain values to express NULL:

UPDATE people SET age = NULL WHERE age = -99;

If every row has version information, such bulk changes create a huge amount of entries in the undo buffers, which consume a lot of memory and are inefficient to operate on and read from.

There is also an added complication – the original approach relies on performing in-place updates. While we can efficiently perform in-place updates on uncompressed data, this is not possible when data is compressed. As DuckDB keeps data compressed, both on-disk and in-memory, in-place updates cannot be performed.

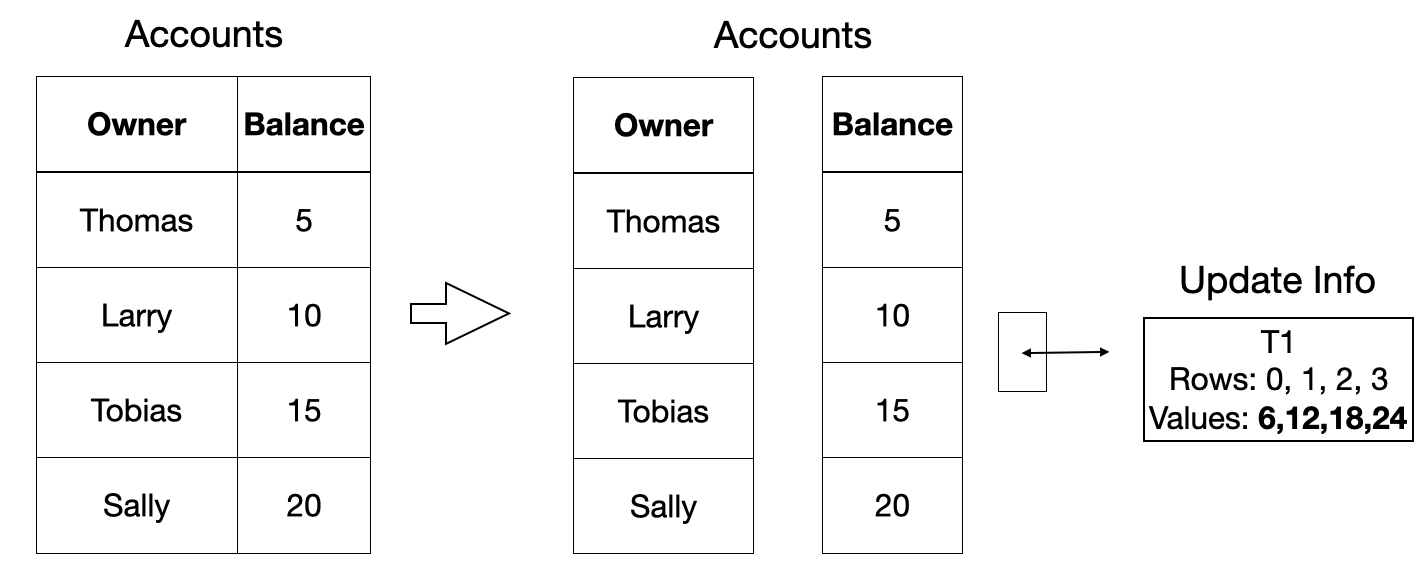

In order to address these issues – DuckDB instead stores bulk version information on a per-column basis. For every batch of 2048 rows, a single version information entry is stored. The version information stores the changes made to the data, instead of the old data, as we cannot modify the original data in-place. Instead, any changes made to the data are flushed to disk during a checkpoint. Below is an illustrated example.

-- add 20% interest to all accounts

UPDATE Accounts SET Balance = Balance + Balance / 5;

One beautiful aspect of this undo buffer scheme is that it is largely performance-transparent: if no changes are made, there are no extra computational cost associated with providing support for transactions. To the best of our knowledge, DuckDB is the only transactional data management system that is optimized for bulk changes to data that are common in analytical use cases. But even with changes present, our transaction scheme is very fast for the kind of transactions that we expect for analytical use cases.

Benchmarks

Here is a small experiment, comparing DuckDB 1.1.0, HyPer 9.1.0, SQLite 3.43.2, and PosgreSQL 14.13 on a recent MacBook Pro, showing some of the effects that an OLAP-optimized transaction scheme will have. We should note that HyPer implements the MVCC scheme from the Neumann paper mentioned above. SQLite does not actually implement MVCC, it is mostly included as a comparison point.

We create two tables with either 1 or 100 columns, each with 10 million rows, containing the integer values 1-100 repeating.

CREATE TABLE mvcc_test_1 (i INTEGER);

INSERT INTO mvcc_test_1

SELECT s1

FROM

generate_series(1, 100) s1(s1),

generate_series(1, 100_000) s2(s2);

CREATE TABLE mvcc_test_100 (i INTEGER,

j1 INTEGER, j2 INTEGER, ..., j99 INTEGER);

INSERT INTO mvcc_test_100

SELECT s1, s1, s1, ..., s1

FROM

generate_series(1, 100) s1(s1),

generate_series(1, 100_000) s2(s2);

We then run three transactions on both tables that increment a single column, with an increasing number of affected rows, 1%, 10% and 100%:

UPDATE mvcc_test_... SET i = i + 1 WHERE i <= 1;

UPDATE mvcc_test_... SET i = i + 1 WHERE i <= 10;

UPDATE mvcc_test_... SET i = i + 1 WHERE i <= 100;

For the single-column case, there should not be huge differences between using a row-major or a column-major concurrency control scheme, and indeed the results show this:

| 1 Column | 1% | 10% | 100% |

|---|---|---|---|

| DuckDB | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.43 |

| SQLite | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.61 |

| HyPer | 0.66 | 0.28 | 2.37 |

| PostgreSQL | 1.44 | 2.48 | 19.07 |

Changing more rows took more time. The rows are small, each row only contain a single value. DuckDB and HyPer, having more modern MVCC scheme based on undo buffers as outlined above, are generally much faster than PostgreSQL. SQLite is doing well, but of course it does not have any MVCC. Timings increase roughly 10× as the amount of rows changed is increased tenfold. So far so good.

For the 100 column case, results look drastically different:

| 100 Columns | 1% | 10% | 100% |

|---|---|---|---|

| DuckDB | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.43 |

| SQLite | 0.51 | 1.79 | 12.93 |

| HyPer | 0.66 | 6.06 | 61.54 |

| PostgreSQL | 1.42 | 5.45 | 50.05 |

Recall that here we are changing a single column out of 100, a common use case in wrangling analytical data sets. Because DuckDB's MVCC scheme is designed for those use cases, it shows exactly the same runtime as in the single-column experiment above. In SQLite, there is a clear impact of the larger row size on the time taken to complete the updates even without MVCC. HyPer and PostgreSQL also show much larger, up to 100× (!) slowdowns as the amount of changed rows is increased.

This neatly brings us to checkpointing.

Write-Ahead Logging and Checkpointing

Any data that's not written to disk but instead still lingers in CPU caches or main memory will be lost in case the operating system crashes or if power is lost. To guarantee durability of changes in the presence of those adverse events, DuckDB needs to ensure that any committed changes are written to persistent storage. However, changes in a transaction can be scattered all over potentially large tables, and fully writing them to disk can be quite slow, especially if it has to happen before any transaction can commit. Also, we don't yet know if we actually want to persist a change, we may encounter a failure in the very process of committing.

The traditional approach of transactional data management systems to balance the requirement of writing changes to persistent storage with the requirement of not taking forever is the write-ahead log (WAL). The WAL can be thought of as a log file of all changes to the database. On each transaction commit, its changes are written to the WAL. On restart, the database files are re-loaded from disk, the changes in the WAL are re-applied (if present), and things happily continue. After some amount of changes, the changes in the WAL need to be physically applied to the table, a process known as “checkpointing”. Afterward, the WAL entries can be discarded, a process known as “truncating”. This scheme ensures that changes persist even if a crash occurs or power is lost immediately after a commit.

DuckDB implements write-ahead logging and you may have seen a .wal file appearing here and there. Checkpointing normally happens automatically whenever the WAL file reached a limit, by default 16 MB but this can be adjusted with the checkpoint_threshold setting. Checkpoints also automatically happen at database shutdown. Checkpoints can also be explicitly triggered with the CHECKPOINT and FORCE CHECKPOINT commands, the difference being that the latter will abort (rollback) any active transactions to ensure the checkpoint is happening right now while the former will wait.

DuckDB explicitly calls the fsync() system call to make sure any WAL entries will be forced to be written to persistent storage, ignoring the many caches on the way. This is necessary because those caches may also be lost in the event of, e.g., power failure, so it's no use to only write log entries to the WAL if they end up not being actually written to storage because the operating system or the disk decided that it was better to wait for performance reasons. However, fsync() does take some time, and while it's generally considered bad practice, there are systems out there that don't do this at all or not by default in order to boast about more transactions per second.

In DuckDB, even bulk loads such as loading large files into tables (e.g., using the COPY statement) are fully transactional. This means you can do something like this:

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

CREATE TABLE people (age INTEGER, ...);

COPY people FROM 'many_people.csv';

UPDATE people SET age = NULL WHERE age = -99;

SELECT

CASE

WHEN (SELECT count(*) FROM people) = 1_000_000 THEN true

ELSE error('expected 1m rows')

END;

COMMIT;

This transaction creates a table, copies a large CSV file into the table, and then updates the table to replace a magic value. Finally, a check is performed to see if there is the expected number of rows in the table. All this is bound together into a single transaction. If anything goes wrong at any point in the process or the check fails, the transaction will be aborted and zero changes to the database will have happened, the table will not even exist. This is great because it allows implementing all-or-nothing semantics for complex loading tasks, possibly into many tables.

However, logging large changes is a problem. Imagine the many_people.csv file being large, say ten gigabytes. As discussed, all changes are written to the WAL and eventually checkpointed. The changes in the file are large enough to immediately trigger a checkpoint. So now we're first writing ten gigabytes to the WAL, and then reading them again, and then writing them again to the database file. Instead of reading ten and writing ten, we have read twenty and written twenty. This is not ideal, but rather than allowing to bypass transactions for bulk loads, DuckDB will instead optimistically write large changes to new blocks in the database file directly, and merely add a reference to the WAL. On commit, these new blocks are added to the table. On rollback, the blocks are marked as free space. So while this can lead to the database file pointlessly increasing in size if transactions are aborted, the common case will benefit greatly. Again, this means that users experience near-zero-cost transactionality.

More Experiments

Making concurrency control and write-ahead looking work correctly in the face of failure is very challenging. Software engineers are biased towards the “happy path”, where everything works as intended. The well-known TPC-H benchmark actually contains tests that stress concurrency and logging schemes (Section 3.5.4, “Durability Tests”). Our previous blog post also implemented this test and DuckDB passed.

In addition, we also defined our own, even more challenging test for durability: we run the TPC-H refresh sets one-by-one, in a sub-process. The sub-process reports the last committed refresh. As they are run, after a random (short) time interval, that sub-process is being killed (using SIGKILL). Then, DuckDB is restarted, it will likely start recovering from WAL and then continue with the refresh sets. Because of the random time interval, it is likely that DuckDB also gets killed during WAL recovery. This of course should not have any impact on the contents of the database. Finally, we have pre-computed the correct result after running 4000 refresh sets using DuckDB, and after all is set and done we check if there are any differences. There were none, luckily.

To stress our implementation further, we have repeated this experiment on a special file system, LazyFS. This FUSE file system is specifically designed to help uncover bugs in database systems by – among other things – not properly flushing changes to disk using fsync(). In our LazyFS configuration, any change that is written to a file is discarded unless sync-ed, which also happens if a file is closed. So in our experiment where we kill the database any un-sync-ed entries in the WAL would be lost. We've re-run our durability tests described above on LazyFS and are also happy to report that no issues were found.

Conclusion

In this post, we described DuckDB's approaches to concurrency control and write-ahead logging. Of course, we are constantly working on improving them. One nasty failure mode that can appear in real-world systems are partial (“torn”) writes to files, where only parts of write requests actually make it to the file. Luckily, LazyFS can be configured to be even more hostile, for example failing read and write system calls entirely, returning partial or wrong data, or only partially writing the data to disk. We plan to expand our experimentation on this, to make sure DuckDB's transaction handling is as bullet-proof as it can be.

And who knows, maybe we even dare to unleash the famous Kyle of Jepsen on DuckDB at some point.