The Lost Decade of Small Data?

TL;DR: We benchmark DuckDB on a 2012 MacBook Pro to decide: did we lose a decade chasing distributed architectures for data analytics?

Much has been said, not in the very least by ourselves, about how data is actually not that “Big” and how the speed of hardware innovation is outpacing the growth of useful datasets. We may have gone so far to predict a data singularity in the near future, where 99% of useful datasets can be comfortably queried on a single node. As it was recently shown, the median scan in Amazon Redshift and Snowflake reads a doable 100 MB of data, and the 99.9-percentile reads less than 300 GB. So the singularity might be closer than we think.

But we started wondering, when did this development really start? When did personal computers like the ubiquitous MacBook Pro, usually condemned to running Chrome, become the data processing powerhouses that they really are today?

Let's turn our attention to the 2012 Retina MacBook Pro, a computer many people (myself included) bought at the time because of its gorgeous “Retina” display. Millions were sold. Despite being unemployed at the time, I had even splurged for the 16 GB RAM upgrade. But there was another often-forgotten revolutionary change in this machine: it was the first MacBook with a built-in Solid-State Disk (SSD) and a competitive 4-core 2.6 GHz “Core i7” CPU. It's funny to watch the announcement again, where they do stress the performance aspect of the “all-flash architecture” as well.

Side note: the MacBook Air was actually the first MacBook with an (optional) built-in SSD already back in 2008. But it did not have the CPU firepower of the Pro, sadly.

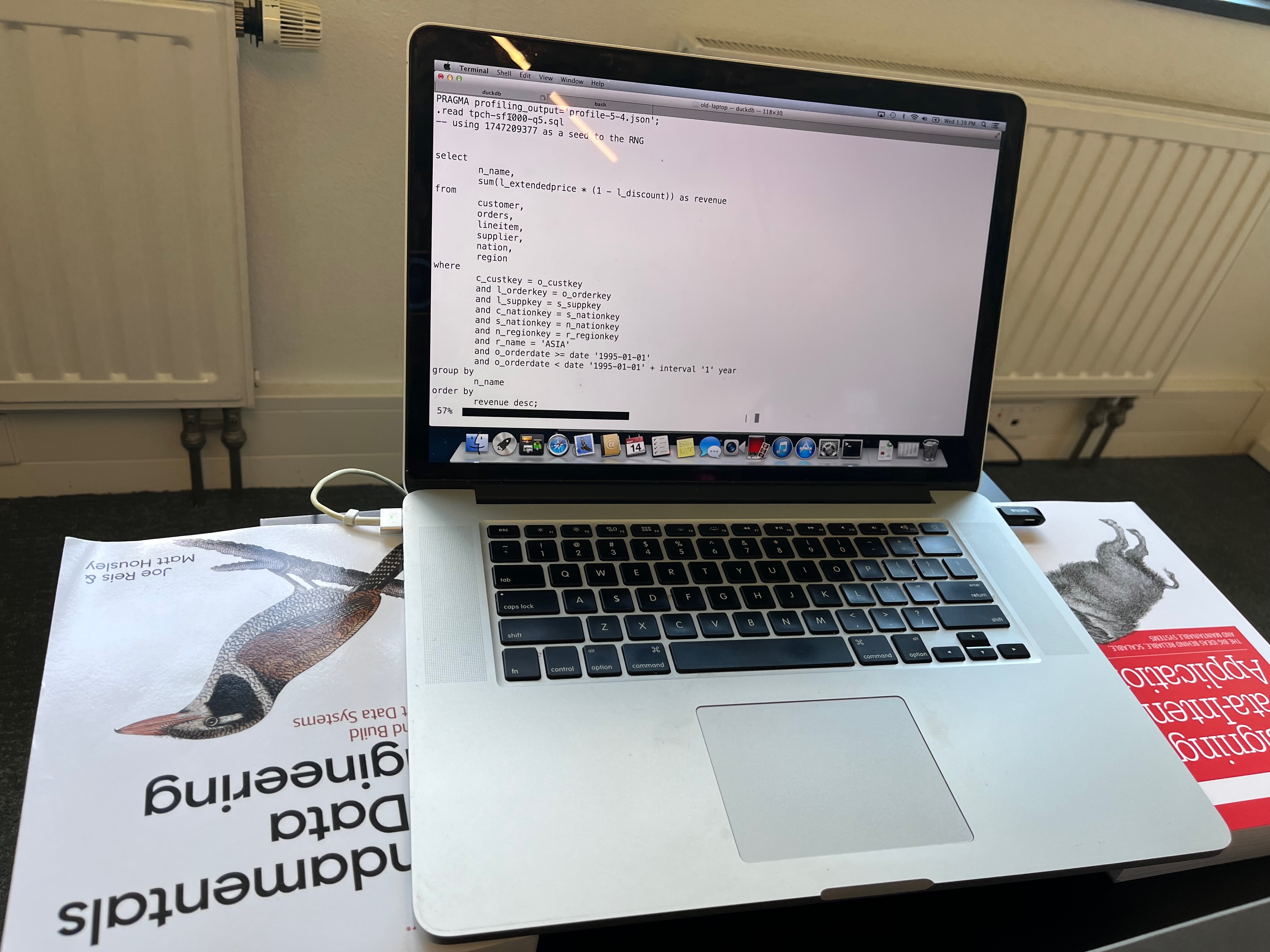

Coincidentally, I still have this laptop in the DuckDB Labs office, currently used by my kids to type their names in a massive font size or watch Bluey on YouTube when they're around. But can this relic still run modern-day DuckDB? How will its performance compare to modern MacBooks? And could we have had the data revolution that we are seeing now already back in 2012? Let's find out!

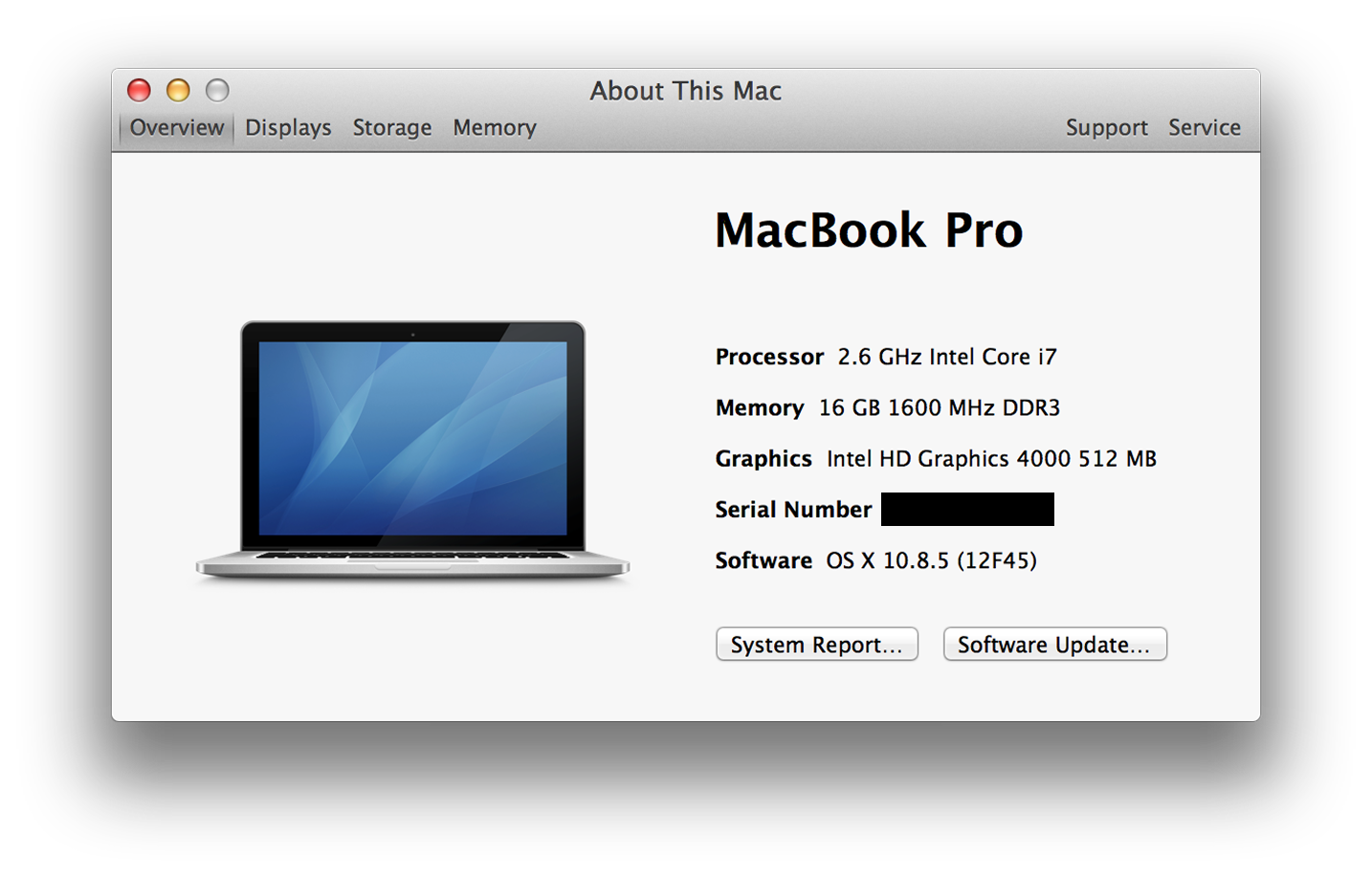

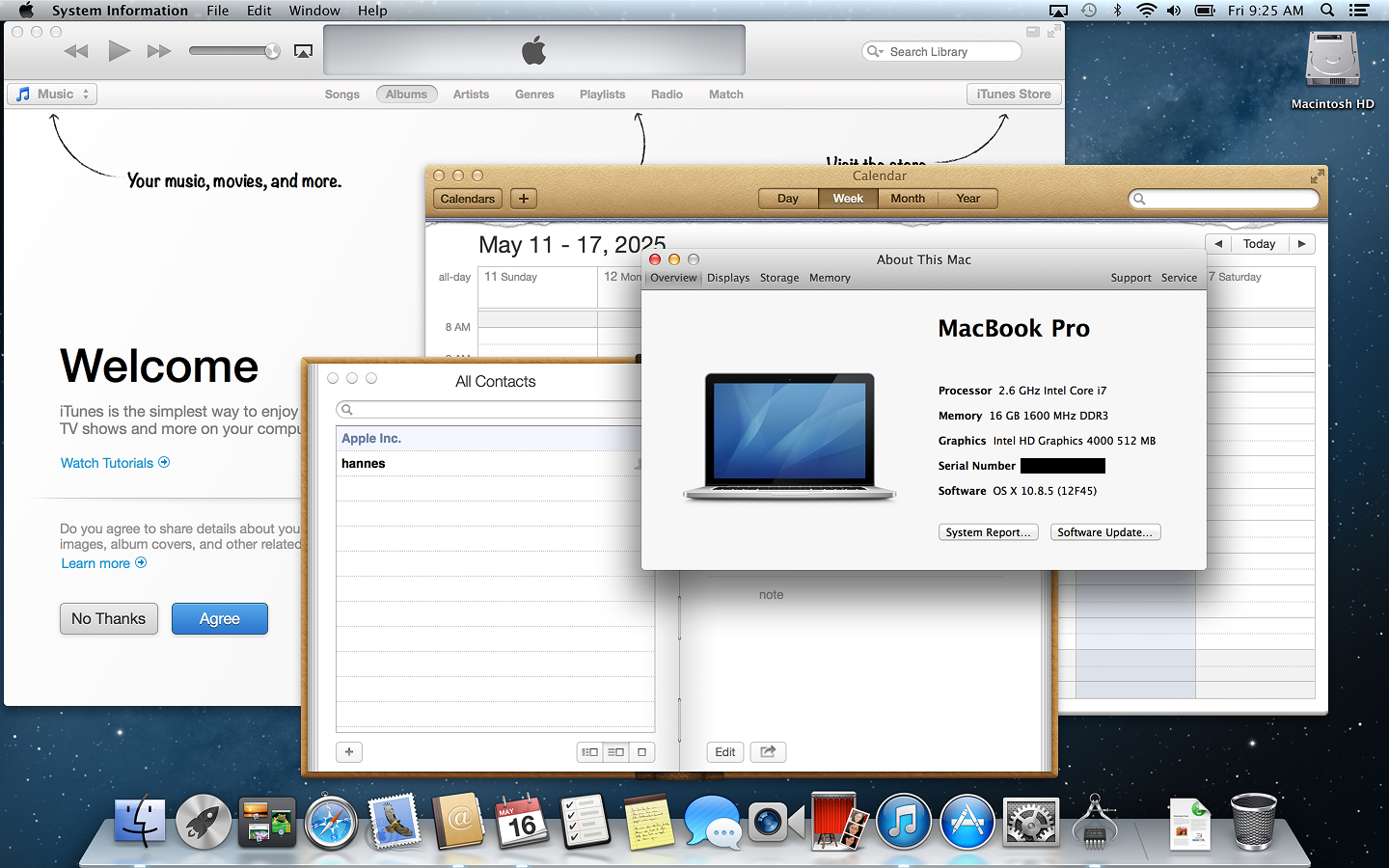

Software

First, what about the operating system? In order to make the comparison fair(er) to the decades, we actually downgraded the operating system on the Retina to OS X 10.8.5 “Mountain Lion”, the operating system version that shipped just a few weeks after the laptop itself in July 2012. Even though the Retina can actually run 10.15 (Catalina), we felt a true 2012 comparison should also use an operating system from the era. Below is a screenshot of the user interface for those of us who sometimes feel a little old.

Moving on to DuckDB itself: here at DuckDB we are more than a little religious about portability and dependencies – or rather the lack thereof. This means that very little had to happen to make DuckDB run on the ancient Mountain Lion: the stock DuckDB binary is built with by default with backwards-compatibility to OS X 11.0 (Big Sur), but simply changing the flag and recompiling turned out to be enough to make DuckDB 1.2.2 run on Mountain Lion. We would have loved to also use a 2012 compiler to build DuckDB, but, alas, C++ 11 was unsurprisingly simply too new in 2012 to be fully supported by compilers. Either way, the binary runs fine and could have been also produced by working around the compiler bugs. Or we could have just hand-coded Assembly like others have done.

Benchmarks

But we're not interested in synthetic CPU scores, we're interested in synthetic SQL scores instead! To see how the old machine is holding up when performing serious data crunching, we used the at this point rather tired but well-known TPC-H benchmark at scale factor 1000. This means that the two main tables, lineitem and orders contain 6 and 1.5 billion rows, respectively. When stored as a DuckDB database, the database has a size of ca. 265 GB.

From the audited results on the TPC website, we can see that running the benchmark on this scale factor on a single node seems to require hardware costing hundreds of thousands of Dollars.

We ran each of the 22 benchmark queries five times, and took the median runtime to remove noise. However, because the amount of RAM (16 GB) is very much less than the database size (265 GB), no significant amount of the input data can be cached in the buffer manager, so those are not really what people sometimes call “hot” runs.

Below are the per-query results in seconds:

| query | latency |

|---|---|

| 1 | 142.2 |

| 2 | 23.2 |

| 3 | 262.7 |

| 4 | 167.5 |

| 5 | 185.9 |

| 6 | 127.7 |

| 7 | 278.3 |

| 8 | 248.4 |

| 9 | 675.0 |

| 10 | 1266.1 |

| 11 | 33.4 |

| 12 | 161.7 |

| 13 | 384.7 |

| 14 | 215.9 |

| 15 | 197.6 |

| 16 | 100.7 |

| 17 | 243.7 |

| 18 | 2076.1 |

| 19 | 283.9 |

| 20 | 200.1 |

| 21 | 1011.9 |

| 22 | 57.7 |

But what do those cold numbers actually mean? The hidden sensation is that we actually have numbers, this old computer could actually complete all benchmark queries using DuckDB! If we look at the time a bit closer, we see the queries take anywhere between a minute and half an hour. Those are not unreasonable waiting times for analytical queries on that sort of data in any way. Heck, you would have been waiting way longer back in 2012 for Hadoop YARN to pick up your job in the first place only to spew stack traces at you at some point.

2023 Improvements

But how do those results stack up against a modern MacBook? As a comparison point, we used a modern ARM-based M3 Max MacBook Pro, which happened to be sitting on the same desk. But between them, the two MacBooks represent more than a decade of hardware development.

Looking at GeekBench 5 benchmark scores alone, we see a ca. 7× difference in raw CPU speed when using all cores, and ca. factor 3 difference in single-core speed. Of course there are also big differences in RAM and SSD speeds. Funnily, the display size and resolution are almost unchanged.

Here are the results side-by-side:

| query | latency_old | latency_new | speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 142.2 | 19.6 | 7.26 |

| 2 | 23.2 | 2.0 | 11.60 |

| 3 | 262.7 | 21.8 | 12.05 |

| 4 | 167.5 | 11.1 | 15.09 |

| 5 | 185.9 | 15.5 | 11.99 |

| 6 | 127.7 | 6.6 | 19.35 |

| 7 | 278.3 | 14.9 | 18.68 |

| 8 | 248.4 | 14.5 | 17.13 |

| 9 | 675.0 | 33.3 | 20.27 |

| 10 | 1266.1 | 23.6 | 53.65 |

| 11 | 33.4 | 2.2 | 15.18 |

| 12 | 161.7 | 10.1 | 16.01 |

| 13 | 384.7 | 24.4 | 15.77 |

| 14 | 215.9 | 9.2 | 23.47 |

| 15 | 197.6 | 8.2 | 24.10 |

| 16 | 100.7 | 4.1 | 24.56 |

| 17 | 243.7 | 15.3 | 15.93 |

| 18 | 2076.1 | 47.6 | 43.62 |

| 19 | 283.9 | 23.1 | 12.29 |

| 20 | 200.1 | 10.9 | 18.36 |

| 21 | 1011.9 | 47.8 | 21.17 |

| 22 | 57.7 | 4.3 | 13.42 |

We do see significant speedups, from 7 up to as much as 53. The geometric mean of the timings improved from 218 to 12, a ca. 20× improvement.

Reproducibility

The binary, scripts, queries, and results are available on GitHub for inspection. We also made the TPC-H SF1000 database file available for download so you don't have to generate it. But be warned, it's a large file.

Discussion

We have seen how the decade-old MacBook Pro Retina has been able to complete a complex analytical benchmark. A newer laptop was able to significantly improve on those times. But absolute speedup numbers are a bit pointless here. The difference is purely quantitative, not qualitative.

From a user perspective, it matters much more that those queries complete in somewhat reasonable time, not if it took 10 or 100 seconds to do so. We can tackle almost the same kind of data problems with both laptops, we just have to be willing to wait a little longer. This is especially true given DuckDB's out-of-core capability, which allows it to spill query intermediates to disks if required.

What is perhaps more interesting is that back in 2012, it would have been completely feasible to have a single-node SQL engine like DuckDB that could run complex analytical SQL queries against a database of 6 billion rows in manageable time – and we did not even have to immerse it in dry ice this time.

History is full of “what if”s, what if something like DuckDB had existed in 2012? The main ingredients were there, vectorized query processing had already been invented in 2005. Would the now somewhat-silly-looking move to distributed systems for data analysis have ever happened? The dataset size of our benchmark database was awfully close to that 99.9% percentile of input data volume for analytical queries in 2024. And while the retina MacBook Pro was a high-end machine in 2012, by 2014 many other vendors shifted to offering laptops with built-in SSD storage and larger amounts of memory became more widespread.

So, yes, we really did lose a full decade.