Fastest Table Sort in the West – Redesigning DuckDB’s Sort

TL;DR: DuckDB, a free and open-source analytical data management system, has a new highly efficient parallel sorting implementation that can sort much more data than fits in main memory.

Database systems use sorting for many purposes, the most obvious purpose being when a user adds an ORDER BY clause to their query.

Sorting is also used within operators, such as window functions.

DuckDB recently improved its sorting implementation, which is now able to sort data in parallel and sort more data than fits in memory.

In this post, we will take a look at how DuckDB sorts, and how this compares to other data management systems.

Not interested in the implementation? Jump straight to the experiments!

Sorting Relational Data

Sorting is one of the most well-studied problems in computer science, and it is an important aspect of data management. There are entire communities dedicated to who sorts fastest. Research into sorting algorithms tends to focus on sorting large arrays or key/value pairs. While important, this does not cover how to implement sorting in a database system. There is a lot more to sorting tables than just sorting a large array of integers!

Consider the following example query on a snippet of a TPC-DS table:

SELECT c_customer_sk, c_birth_country, c_birth_year

FROM customer

ORDER BY c_birth_country DESC,

c_birth_year ASC NULLS LAST;

Which yields:

| c_customer_sk | c_birth_country | c_birth_year |

|---|---|---|

| 64760 | NETHERLANDS | 1991 |

| 75011 | NETHERLANDS | 1992 |

| 89949 | NETHERLANDS | 1992 |

| 90766 | NETHERLANDS | NULL |

| 42927 | GERMANY | 1924 |

In other words: c_birth_country is ordered descendingly, and where c_birth_country is equal, we sort on c_birth_year ascendingly.

By specifying NULLS LAST, null values are treated as the lowest value in the c_birth_year column.

Whole rows are thus reordered, not just the columns in the ORDER BY clause. The columns that are not in the ORDER BY clause we call "payload columns".

Therefore, payload column c_customer_sk has to be reordered too.

It is easy to implement something that can evaluate the example query using any sorting implementation, for instance, C++'s std::sort.

While std::sort is excellent algorithmically, it is still a single-threaded approach that is unable to efficiently sort by multiple columns because function call overhead would quickly dominate sorting time.

Below we will discuss why that is.

To achieve good performance when sorting tables, a custom sorting implementation is needed. We are – of course – not the first to implement relational sorting, so we dove into the literature to look for guidance.

In 2006 the famous Goetz Graefe wrote a survey on implementing sorting in database systems. In this survey, he collected many sorting techniques that are known to the community. This is a great guideline if you are about to start implementing sorting for tables.

The cost of sorting is dominated by comparing values and moving data around. Anything that makes these two operations cheaper will have a big impact on the total runtime.

There are two obvious ways to go about implementing a comparator when we have multiple ORDER BY clauses:

- Loop through the clauses: Compare columns until we find one that is not equal, or until we have compared all columns. This is fairly complex already, as this requires a loop with an if/else inside of it for every single row of data. If we have columnar storage, this comparator has to jump between columns, causing random access in memory.

- Entirely sort the data by the first clause, then sort by the second clause, but only where the first clause was equal, and so on. This approach is especially inefficient when there are many duplicate values, as it requires multiple passes over the data.

Binary String Comparison

The binary string comparison technique improves sorting performance by simplifying the comparator. It encodes all columns in the ORDER BY clause into a single binary sequence that, when compared using memcmp will yield the correct overall sorting order. Encoding the data is not free, but since we are using the comparator so much during sorting, it will pay off.

Let us take another look at 3 rows of the example:

| c_birth_country | c_birth_year |

|---|---|

| NETHERLANDS | 1991 |

| NETHERLANDS | 1992 |

| GERMANY | 1924 |

On little-endian hardware, the bytes that represent these values look like this in memory, assuming 32-bit integer representation for the year:

c_birth_country

-- NETHERLANDS

01001110 01000101 01010100 01001000 01000101 01010010 01001100 01000001 01001110 01000100 01010011 00000000

-- GERMANY

01000111 01000101 01010010 01001101 01000001 01001110 01011001 00000000

c_birth_year

-- 1991

11000111 00000111 00000000 00000000

-- 1992

11001000 00000111 00000000 00000000

-- 1924

10000100 00000111 00000000 00000000

The trick is to convert these to a binary string that encodes the sorting order:

-- NETHERLANDS | 1991

10110001 10111010 10101011 10110111 10111010 10101101 10110011 10111110 10110001 10111011 10101100 11111111

10000000 00000000 00000111 11000111

-- NETHERLANDS | 1992

10110001 10111010 10101011 10110111 10111010 10101101 10110011 10111110 10110001 10111011 10101100 11111111

10000000 00000000 00000111 11001000

-- GERMANY | 1924

10111000 10111010 10101101 10110010 10111110 10110001 10100110 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111

10000000 00000000 00000111 10000100

The binary string is fixed-size because this makes it much easier to move it around during sorting.

The string "GERMANY" is shorter than "NETHERLANDS", therefore it is padded with 00000000's.

All bits in column c_birth_country are subsequently inverted because this column is sorted descendingly.

If a string is too long we encode its prefix and only look at the whole string if the prefixes are equal.

The bytes in c_birth_year are swapped because we need the big-endian representation to encode the sorting order.

The first bit is also flipped, to preserve order between positive and negative integers for signed integers.

If there are NULL values, these must be encoded using an additional byte (not shown in the example).

With this binary string, we can now compare both columns at the same time by comparing only the binary string representation.

This can be done with a single memcmp in C++! The compiler will emit efficient assembly for single function call, even auto-generating SIMD instructions.

This technique solves one of the problems mentioned above, namely the function call overhead when using complex comparators.

Radix Sort

Now that we have a cheap comparator, we have to choose our sorting algorithm. Every computer science student learns about comparison-based sorting algorithms like Quicksort and Merge sort, which have O (n log n) time complexity, where n is the number of records being sorted.

However, there are also distribution-based sorting algorithms, which typically have a time complexity of O (n k), where k is the width of the sorting key. This class of sorting algorithms scales much better with a larger n because k is constant, whereas log n is not.

One such algorithm is Radix sort. This algorithm sorts the data by computing the data distribution with Counting sort, multiple times until all digits have been counted.

It may sound counter-intuitive to encode the sorting key columns such that we have a cheap comparator, and then choose a sorting algorithm that does not compare records.

However, the encoding is necessary for Radix sort: Binary strings that produce a correct order with memcmp will produce a correct order if we do a byte-by-byte Radix sort.

Two-Phase Parallel Sorting

DuckDB uses Morsel-Driven Parallelism, a framework for parallel query execution. For the sorting operator, this means that multiple threads collect roughly an equal amount of data, in parallel, from the table.

We use this parallelism for sorting by first having each thread sort the data it collects using our Radix sort. After this first sorting phase, each thread has one or more sorted blocks of data, which must be combined into the final sorted result. Merge sort is the algorithm of choice for this task. There are two main ways of implementing merge sort: K-way merge and Cascade merge.

K-way merge merges K lists into one sorted list in one pass, and is traditionally used for external sorting (sorting more data than fits in memory) because it minimizes I/O. Cascade merge merges two lists of sorted data at a time until only one sorted list remains, and is used for in-memory sorting because it is more efficient than K-way merge. We aim to have an implementation that has high in-memory performance, which gracefully degrades as we go over the limit of available memory. Therefore, we choose cascade merge.

In a cascade merge sort, we merge two blocks of sorted data at a time until only one sorted block remains. Naturally, we want to use all available threads to compute the merge. If we have many more sorted blocks than threads, we can assign each thread to merge two blocks. However, as the blocks get merged, we will not have enough blocks to keep all threads busy. This is especially slow when the final two blocks are merged: One thread has to process all the data.

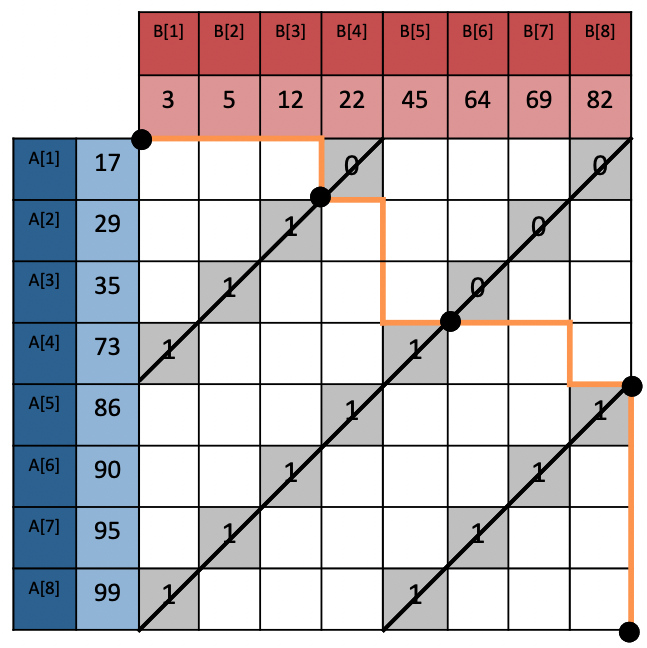

To fully parallelize this phase, we have implemented Merge Path by Oded Green et al. Merge Path pre-computes where the sorted lists will intersect while merging, shown in the image below (taken from the paper).

The intersections along the merge path can be efficiently computed using Binary Search. If we know where the intersections are, we can merge partitions of the sorted data independently in parallel. This allows us to use all available threads effectively for the entire merge phase. For another trick to improve merge sort, see the appendix.

Columns or Rows?

Besides comparisons, the other big cost of sorting is moving data around. DuckDB has a vectorized execution engine. Data is stored in a columnar layout, which is processed in batches (called chunks) at a time. This layout is great for analytical query processing because the chunks fit in the CPU cache, and it gives a lot of opportunities for the compiler to generate SIMD instructions. However, when the table is sorted, entire rows are shuffled around, rather than columns.

We could stick to the columnar layout while sorting: Sort the key columns, then re-order the payload columns one by one. However, re-ordering will cause a random access pattern in memory for each column. If there are many payload columns, this will be slow. Converting the columns to rows will make re-ordering rows much easier. This conversion is of course not free: Columns need to be copied to rows, and back from rows to columns again after sorting.

Because we want to support external sorting, we have to store data in buffer-managed blocks that can be offloaded to disk. Because we have to copy the input data to these blocks anyway, converting the rows to columns is effectively free.

There are a few operators that are inherently row-based, such as joins and aggregations. DuckDB has a unified internal row layout for these operators, and we decided to use it for the sorting operator as well. This layout has only been used in memory so far. In the next section, we will explain how we got it to work on disk as well. We should note that we will only write sorting data to disk if main memory is not able to hold it.

External Sorting

The buffer manager can unload blocks from memory to disk. This is not something we actively do in our sorting implementation, but rather something that the buffer manager decides to do if memory would fill up otherwise. It uses a least-recently-used queue to decide which blocks to write. More on how to properly use this queue in the appendix.

When we need a block, we "pin" it, which reads it from disk if it is not loaded already. Accessing disk is much slower than accessing memory, therefore it is crucial that we minimize the number of reads and writes.

Unloading data to disk is easy for fixed-size columns like integers, but more difficult for variable-sized columns like strings. Our row layout uses fixed-size rows, which cannot fit strings with arbitrary sizes. Therefore, strings are represented by a pointer, which points into a separate block of memory where the actual string data lives, a so-called "string heap".

We have changed our heap to also store strings row-by-row in buffer-managed blocks:

Each row has an additional 8-byte field pointer which points to the start of this row in the heap.

This is useless in the in-memory representation, but we will see why it is useful for the on-disk representation in just a second.

If the data fits in memory, the heap blocks stay pinned, and only the fixed-size rows are re-ordered while sorting. If the data does not fit in memory, the blocks need to be offloaded to disk, and the heap will also be re-ordered while sorting. When a heap block is offloaded to disk, the pointers pointing into it are invalidated. When we load the block back into memory, the pointers will have changed.

This is where our row-wise layout comes into play.

The 8-byte pointer field is overwritten with an 8-byte offset field, denoting where in the heap block strings of this row can be found.

This technique is called "pointer swizzling".

When we swizzle the pointers, the row layout and heap block look like this:

The pointers to the subsequent string values are also overwritten with an 8-byte relative offset, denoting how far this string is offset from the start of the row in the heap (hence every stringA has an offset of 0: It is the first string in the row).

Using relative offsets within rows rather than absolute offsets is very useful during sorting, as these relative offsets stay constant, and do not need to be updated when a row is copied.

When the blocks need to be scanned to read the sorted result, we "unswizzle" the pointers, making them point to the string again.

With this dual-purpose row-wise representation, we can easily copy around both the fixed-size rows and the variable-sized rows in the heap. Besides having the buffer manager load/unload blocks, the only difference between in-memory and external sorting is that we swizzle/unswizzle pointers to the heap blocks, and copy data from the heap blocks during merge sort.

All this reduces overhead when blocks need to be moved in and out of memory, which will lead to graceful performance degradation as we approach the limit of available memory.

Comparison with Other Systems

Now that we have covered most of the techniques that are used in our sorting implementation, we want to know how we compare to other systems. DuckDB is often used for interactive data analysis, and is therefore often compared to tools like dplyr.

In this setting, people are usually running on laptops or PCs, therefore we will run these experiments on a 2020 MacBook Pro. This laptop has an Apple M1 CPU, which is ARM-based. The M1 processor has 8 cores: 4 high-performance (Firestorm) cores, and 4 energy-efficient (Icestorm) cores. The Firestorm cores have very, very fast single-thread performance, so this should level the playing field between single- and multi-threaded sorting implementations somewhat. The MacBook has 16 GB of memory, and one of the fastest SSDs found in a laptop.

We will be comparing against the following systems:

- ClickHouse, version 21.7.5

- HyPer, version 2021.2.1.12564

- Pandas, version 1.3.2

- SQLite, version 3.36.0

ClickHouse and HyPer are included in our comparison because they are analytical SQL engines with an emphasis on performance. Pandas and SQLite are included in our comparison because they can be used to perform relational operations within Python, like DuckDB. Pandas operates fully in memory, whereas SQLite is a more traditional disk-based system. This list of systems should give us a good mix of single-/multi-threaded, and in-memory/external sorting.

ClickHouse was built for M1 using this guide.

We have set the memory limit to 12 GB, and max_bytes_before_external_sort to 10 GB, following this suggestion.

HyPer is Tableau's data engine, created by the database group at the University of Munich. It does not run natively (yet) on ARM-based processors like the M1. We will use Rosetta 2, macOS's x86 emulator to run it. Emulation causes some overhead, so we have included an experiment on an x86 machine in the appendix.

Benchmarking sorting in database systems is not straightforward. Ideally, we would like to measure only the time it takes to sort the data, not the time it takes to read the input data and show the output. Not every system has a profiler to measure the time of the sorting operator exactly, so this is not an option.

To approach a fair comparison, we will measure the end-to-end time of queries that sort the data and write the result to a temporary table, i.e.:

CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE output AS

SELECT ...

FROM ...

ORDER BY ...;

There is no perfect solution to this problem, but this should give us a good comparison because the end-to-end time of this query should be dominated by sorting.

For Pandas we will use sort_values with inplace=False to mimic this query.

In ClickHouse, temporary tables can only exist in memory, which is problematic for our out-of-core experiments.

Therefore we will use a regular TABLE, but then we also need to choose a table engine.

Most of the table engines apply compression or create an index, which we do not want to measure.

Therefore we have chosen the simplest on-disk engine, which is File, with format Native.

The table engine we chose for the input tables for ClickHouse is MergeTree with ORDER BY tuple().

We chose this because we encountered strange behavior with File(Native) input tables, where there was no difference in runtime between the queries SELECT * FROM ... ORDER BY and SELECT col1 FROM ... ORDER BY.

Presumably, because all columns in the table were sorted regardless of how many there were selected.

To measure stable end-to-end query time, we run each query 5 times and report the median run time. There are some differences in reading/writing tables between the systems. For instance, Pandas cannot read/write from/to disk, so both the input and output data frame will be in memory. DuckDB will not write the output table to disk unless there is not enough room to keep it in memory, and therefore also may have an advantage. However, sorting dominates the total runtime, so these differences are not that impactful.

Random Integers

We will start with a simple example. We have generated the first 100 million integers and shuffled them, and we want to know how well the systems can sort them. This experiment is more of a micro-benchmark than anything else and is of little real-world significance.

For our first experiment, we will look at how the systems scale with the number of rows. From the initial table with integers, we have made 9 more tables, with 10M, 20M, …, 90M integers each.

Being a traditional disk-based database system, SQLite always opts for an external sorting strategy. It writes intermediate sorted blocks to disk even if they fit in main-memory, therefore it is much slower. The performance of the other systems is in the same ballpark, with DuckDB and ClickHouse going toe-to-toe with ~3 and ~4 seconds for 100M integers. Because SQLite is so much slower, we will not include it in our next set of experiments (TPC-DS).

DuckDB and ClickHouse both make very good use out of all available threads, with a single-threaded sort in parallel, followed by a parallel merge sort. We are not sure what strategy HyPer uses. For our next experiment, we will zoom in on multi-threading, and see how well ClickHouse and DuckDB scale with the number of threads (we were not able to set the number of threads for HyPer).

This plot demonstrates that Radix sort is very fast. DuckDB sorts 100M integers in just under 5 seconds using a single thread, which is much faster than ClickHouse. Adding threads does not improve performance as much for DuckDB, because Radix Sort is so much faster than Merge Sort. Both systems end up at about the same performance at 4 threads.

Beyond 4 threads we do not see performance improve much more, due to the CPU architecture. For all of the of other the experiments, we have set both DuckDB and ClickHouse to use 4 threads.

For our last experiment with random integers, we will see how the sortedness of the input may impact performance. This is especially important to do in systems that use Quicksort because Quicksort performs much worse on inversely sorted data than on random data.

Not surprisingly, all systems perform better on sorted data, sometimes by a large margin. ClickHouse, Pandas, and SQLite likely have some optimization here: e.g., keeping track of sortedness in the catalog, or checking sortedness while scanning the input. DuckDB and HyPer have only a very small difference in performance when the input data is sorted, and do not have such an optimization. For DuckDB the slightly improved performance can be explained due to a better memory access pattern during sorting: When the data is already sorted the access pattern is mostly sequential.

Another interesting result is that DuckDB sorts data faster than some of the other systems can read already sorted data.

TPC-DS

For the next comparison, we have improvised a relational sorting benchmark on two tables from the standard TPC Decision Support benchmark (TPC-DS).

TPC-DS is challenging for sorting implementations because it has wide tables (with many columns, unlike the tables in TPC-H), and a mix of fixed- and variable-sized types.

The number of rows increases with the scale factor.

The tables used here are catalog_sales and customer.

catalog_sales has 34 columns, all fixed-size types (integer and double), and grows to have many rows as the scale factor increases.

customer has 18 columns (10 integers, and 8 strings), and a decent amount of rows as the scale factor increases.

The row counts of both tables at each scale factor are shown in the table below.

| SF | customer | catalog_sales |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100,000 | 1,441,548 |

| 10 | 500,000 | 14,401,261 |

| 100 | 2,000,000 | 143,997,065 |

| 300 | 5,000,000 | 260,014,080 |

We will use customer at SF100 and SF300, which fits in memory at every scale factor.

We will use catalog_sales table at SF10 and SF100, which does not fit in memory anymore at SF100.

The data was generated using DuckDB's TPC-DS extension, then exported to CSV in a random order to undo any ordering patterns that could have been in the generated data.

Catalog Sales (Numeric Types)

Our first experiment on the catalog_sales table is selecting 1 column, then 2 columns, …, up to all 34, always ordering by cs_quantity and cs_item_sk.

This experiment will tell us how well the different systems can re-order payload columns.

We see similar trends at SF10 and SF100, but for SF100, at around 12 payload columns or so, the data does not fit in memory anymore, and ClickHouse and HyPer show a big drop in performance. ClickHouse switches to an external sorting strategy, which is much slower than its in-memory strategy. Therefore, adding a few payload columns results in a runtime that is orders of magnitude higher. At 20 payload columns ClickHouse runs into the following error:

DB::Exception: Memory limit (for query) exceeded: would use 11.18 GiB (attempt to allocate chunk of 4204712 bytes), maximum: 11.18 GiB: (while reading column cs_list_price): (while reading from part ./store/523/5230c288-7ed5-45fa-9230-c2887ed595fa/all_73_108_2/ from mark 4778 with max_rows_to_read = 8192): While executing MergeTreeThread.

HyPer also drops in performance before erroring out with the following message:

ERROR: Cannot allocate 333982248 bytes of memory: The `global memory limit` limit of 12884901888 bytes was exceeded.

As far as we are aware, HyPer uses mmap, which creates a mapping between memory and a file.

This allows the operating system to move data between memory and disk.

While useful, it is no substitute for a proper external sort, as it creates random access to disk, which is very slow.

Pandas performs surprisingly well on SF100, despite the data not fitting in memory. Pandas can only do this because macOS dynamically increases swap size. Most operating systems do not do this and would fail to load the data at all. Using swap usually slows down processing significantly, but the SSD is so fast that there is no visible performance drop!

While Pandas loads the data, swap size grows to an impressive ~40 GB: Both the file and the data frame are fully in memory/swap at the same time, rather than streamed into memory. This goes down to ~20 GB of memory/swap when the file is done being read. Pandas is able to get quite far into the experiment until it crashes with the following error:

UserWarning: resource_tracker: There appear to be 1 leaked semaphore objects to clean up at shutdown

DuckDB performs well both in-memory and external, and there is no clear visible point at which data no longer fits in memory: Runtime is fast and reliable.

Customer (Strings & Integers)

Now that we have seen how the systems handle large amounts of fixed-size types, it is time to see some variable-size types!

For our first experiment on the customer table, we will select all columns, and order them by either 3 integer columns (c_birth_year, c_birth_month, c_birth_day), or by 2 string columns (c_first_name, c_last_name).

Comparing strings is much, much more difficult than comparing integers, because strings can have variable sizes, and need to be compare byte-by-byte, whereas integers always have the same comparison.

As expected, ordering by strings is more expensive than ordering by integers, except for HyPer, which is impressive.

Pandas has only a slightly bigger difference between ordering by integers and ordering by strings than ClickHouse and DuckDB.

This difference is explained by an expensive comparator between strings.

Pandas uses NumPy's sort, which is efficiently implemented in C.

However, when this sorts strings, it has to use virtual function calls to compare a Python string object, which is slower than a simple "<" between integers in C.

Nevertheless, Pandas performs well on the customer table.

In our next experiment, we will see how the payload type affects performance.

customer has 10 integer columns and 8 string columns.

We will either select all integer columns or all string columns and order by (c_birth_year, c_birth_month, c_birth_day) every time.

As expected, re-ordering strings takes much more time than re-ordering integers. Pandas has an advantage here because it already has the strings in memory, and most likely only needs to re-order pointers to these strings. The database systems need to copy strings twice: Once when reading the input table, and again when creating the output table. Profiling in DuckDB reveals that the actual sorting takes less than a second at SF300, and most time is spent on (de)serializing strings.

Conclusion

DuckDB's new parallel sorting implementation can efficiently sort more data than fits in memory, making use of the speed of modern SSDs. Where other systems crash because they run out of memory, or switch to an external sorting strategy that is much slower, DuckDB's performance gracefully degrades as it goes over the memory limit.

The code that was used to run the experiments can be found on GitHub. If we made any mistakes, please let us know!

DuckDB is a free and open-source database management system (MIT licensed). It aims to be the SQLite for Analytics, and provides a fast and efficient database system with zero external dependencies. It is available not just for Python, but also for C/C++, R, Java, and more.

Discuss this post on Hacker News

Read our paper on sorting at ICDE '23

Listen to Laurens' appearance on the Disseminate podcast:

Appendix A: Predication

Another technique we have used to speed up merge sort is predication. With this technique, we turn code with if/else branches into code without branches. Modern CPUs try to predict whether the if, or the else branch will be predicted. If this is hard to predict, it can slow down the code. Take a look at the example of pseudo-code with branches below.

// continue until merged

while (l_ptr && r_ptr) {

// check which side is smaller

if (memcmp(l_ptr, r_ptr, entry) < 0) {

// copy from left side and advance

memcpy(result_ptr, l_ptr, entry);

l_ptr += entry;

} else {

// copy from right side and advance

memcpy(result_ptr, r_ptr, entry);

r_ptr += entry;

}

// advance result

result_ptr += entry;

}

We are merging the data from the left and right blocks into a result block, one entry at a time, by advancing pointers. This code can be made branchless by using the comparison boolean as a 0 or 1, shown in the pseudo-code below.

// continue until merged

while (l_ptr && r_ptr) {

// store comparison result in a bool

bool left_less = memcmp(l_ptr, r_ptr, entry) < 0;

bool right_less = 1 - left_less;

// copy from either side

memcpy(result_ptr, l_ptr, left_less * entry);

memcpy(result_ptr, r_ptr, right_less * entry);

// advance either one

l_ptr += left_less * entry;

l_ptr += right_less * entry;

// advance result

result_ptr += entry;

}

When left_less is true, it is equal to 1.

This means right_less is false, and therefore equal to 0.

We use this to copy entry bytes from the left side, and 0 bytes from the right side, and incrementing the left and right pointers accordingly.

With predicated code, the CPU does not have to predict which instructions to execute, which means there will be fewer instruction cache misses!

Appendix B: Zig-Zagging

A simple trick to reduce I/O is zig-zagging through the pairs of blocks to merge in the cascaded merge sort. This is illustrated in the image below (dashes arrows indicate in which order the blocks are merged).

By zig-zagging through the blocks, we start an iteration by merging the last blocks that were merged in the previous iteration. Those blocks are likely still in memory, saving us some precious read/write operations.

Appendix C: x86 Experiment

We also ran the catalog_sales SF100 experiment on a machine with x86 CPU architecture, to get a more fair comparison with HyPer (without Rosetta 2 emulation).

The machine has an Intel(R) Xeon(R) W-2145 CPU @ 3.70 GHz, which has 8 cores (up to 16 virtual threads), and 128 GB of RAM, so this time the data fits fully in memory.

We have set the number of threads that DuckDB and ClickHouse use to 8 because we saw no visibly improved performance past 8.

Pandas performs comparatively worse than on the MacBook, because it has a single-threaded implementation, and this CPU has a lower single-thread performance. Again, Pandas crashes with an error (this machine does not dynamically increase swap):

numpy.core._exceptions.MemoryError: Unable to allocate 6.32 GiB for an array with shape (6, 141430723) and data type float64

DuckDB, HyPer, and ClickHouse all make good use out of more available threads, being significantly faster than on the MacBook.

An interesting pattern in this plot is that DuckDB and HyPer scale very similarly with additional payload columns. Although DuckDB is faster at sorting, re-ordering the payload seems to cost about the same for both systems. Therefore it is likely that HyPer also uses a row layout.

ClickHouse scales worse with additional payload columns. ClickHouse does not use a row layout, and therefore has to pay the cost of random access as each column is re-ordered after sorting.