Lightweight Compression in DuckDB

TL;DR: DuckDB supports efficient lightweight compression that is automatically used to keep data size down without incurring high costs for compression and decompression.

When working with large amounts of data, compression is critical for reducing storage size and egress costs. Compression algorithms typically reduce data set size by 75-95%, depending on how compressible the data is. Compression not only reduces the storage footprint of a data set, but also often improves performance as less data has to be read from disk or over a network connection.

Column store formats, such as DuckDB's native file format or Parquet, benefit especially from compression. That is because data within an individual column is generally very similar, which can be exploited effectively by compression algorithms. Storing data in row-wise format results in interleaving of data of different columns, leading to lower compression rates.

DuckDB added support for compression at the end of last year. As shown in the table below, the compression ratio of DuckDB has continuously improved since then and is still actively being improved. In this blog post, we discuss how compression in DuckDB works, and the design choices and various trade-offs that we have made while implementing compression for DuckDB's storage format.

| Version | Taxi | On Time | lineitem |

Notes | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DuckDB v0.2.8 | 15.3 GB | 1.73 GB | 0.85 GB | Uncompressed | July 2021 |

| DuckDB v0.2.9 | 11.2 GB | 1.25 GB | 0.79 GB | RLE + Constant | September 2021 |

| DuckDB v0.3.2 | 10.8 GB | 0.98 GB | 0.56 GB | Bitpacking | February 2022 |

| DuckDB v0.3.3 | 6.9 GB | 0.23 GB | 0.32 GB | Dictionary | April 2022 |

| DuckDB v0.5.0 | 6.6 GB | 0.21 GB | 0.29 GB | FOR | September 2022 |

| DuckDB dev | 4.8 GB | 0.21 GB | 0.17 GB | FSST + Chimp | now() |

| CSV | 17.0 GB | 1.11 GB | 0.72 GB | ||

| Parquet (Uncompressed) | 4.5 GB | 0.12 GB | 0.31 GB | ||

| Parquet (Snappy) | 3.2 GB | 0.11 GB | 0.18 GB | ||

| Parquet (ZSTD) | 2.6 GB | 0.08 GB | 0.15 GB |

Compression Intro

At its core, compression algorithms try to find patterns in a data set in order to store it more cleverly. Compressibility of a data set is therefore dependent on whether or not such patterns can be found, and whether they exist in the first place. Data that follows a fixed pattern can be compressed significantly. Data that does not have any patterns, such as random noise, cannot be compressed. Formally, the compressibility of a dataset is known as its entropy.

As an example of this concept, let us consider the following two data sets.

The constant data set can be compressed by simply storing the value of the pattern and how many times the pattern repeats (e.g., 1x8). The random noise, on the other hand, has no pattern, and is therefore not compressible.

General Purpose Compression Algorithms

The compression algorithms that most people are familiar with are general purpose compression algorithms, such as zip, gzip or zstd. General purpose compression algorithms work by finding patterns in bits. They are therefore agnostic to data types, and can be used on any stream of bits. They can be used to compress files, but they can also be applied to arbitrary data sent over a socket connection.

General purpose compression is flexible and very easy to set up. There are a number of high quality libraries available (such as zstd, snappy or lz4) that provide compression, and they can be applied to any data set stored in any manner.

The downside of general purpose compression is that (de)compression is generally expensive. While this does not matter if we are reading and writing from a hard disk or over a slow internet connection, the speed of (de)compression can become a bottleneck when data is stored in RAM.

Another downside is that these libraries operate as a black box. They operate on streams of bits, and do not reveal information of their internal state to the user. While that is not a problem if you are only looking to decrease the size of your data, it prevents the system from taking advantage of the patterns found by the compression algorithm during execution.

Finally, general purpose compression algorithms work better when compressing large chunks of data. As illustrated in the table below, compression ratios suffer significantly when compressing small amounts of data. To achieve a good compression ratio, blocks of at least 256 kB must be used.

| Compression | 1 kB | 4 kB | 16 kB | 64 kB | 256 kB | 1 MB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| zstd | 1.72 | 2.1 | 2.21 | 2.41 | 2.54 | 2.73 |

| lz4 | 1.29 | 1.5 | 1.52 | 1.58 | 1.62 | 1.64 |

| gzip | 1.7 | 2.13 | 2.28 | 2.49 | 2.62 | 2.67 |

This is relevant because the block size is the minimum amount of data that must be decompressed when reading a single row from disk. Worse, as DuckDB compresses data on a per-column basis, the block size would be the minimum amount of data that must be decompressed per column. With a block size of 256 kB, fetching a single row could require decompressing multiple megabytes of data. This can cause queries that fetch a low number of rows, such as SELECT * FROM tbl LIMIT 5 or SELECT * FROM tbl WHERE id = 42 to incur significant costs, despite appearing to be very cheap on the surface.

Lightweight Compression Algorithms

Another option for achieving compression is to use specialized lightweight compression algorithms. These algorithms also operate by finding patterns in data. However, unlike general purpose compression, they do not attempt to find generic patterns in bitstreams. Instead, they operate by finding specific patterns in data sets.

By detecting specific patterns, specialized compression algorithms can be significantly more lightweight, providing much faster compression and decompression. In addition, they can be effective on much smaller data sizes. This allows us to decompress a few rows at a time, rather than requiring large blocks of data to be decompressed at once. These specialized compression algorithms can also offer efficient support for random seeks, making data access through an index significantly faster.

Lightweight compression algorithms also provide us with more fine-grained control over the compression process. This is especially relevant for us as DuckDB's file format uses fixed-size blocks in order to avoid fragmentation for workloads involving deletes and updates. The fine-grained control allows us to fill these blocks more effectively, and avoid having to guess how much compressed data will fit into a buffer.

On the flip side, these algorithms are ineffective if the specific patterns they are designed for do not occur in the data. As a result, individually, these lightweight compression algorithms are no replacement for general purpose algorithms. Instead, multiple specialized algorithms must be combined in order to capture many different common patterns in data sets.

Compression Framework

Because of the advantages described above, DuckDB uses only specialized lightweight compression algorithms. As each of these algorithms work optimally on different patterns in the data, DuckDB's compression framework must first decide on which algorithm to use to store the data of each column.

DuckDB's storage splits tables into Row Groups. These are groups of 120K rows, stored in columnar chunks called Column Segments. This storage layout is similar to Parquet – but with an important difference: columns are split into blocks of a fixed-size. This design decision was made because DuckDB's storage format supports in-place ACID modifications to the storage format, including deleting and updating rows, and adding and dropping columns. By partitioning data into fixed size blocks the blocks can be easily reused after they are no longer required and fragmentation is avoided.

The compression framework operates within the context of the individual Column Segments. It operates in two phases. First, the data in the column segment is analyzed. In this phase, we scan the data in the segment and find out the best compression algorithm for that particular segment. After that, the compression is performed, and the compressed data is written to the blocks on disk.

While this approach requires two passes over the data within a segment, this does not incur a significant cost, as the amount of data stored in one segment is generally small enough to fit in the CPU caches. A sampling approach for the analyze step could also be considered, but in general we value choosing the best compression algorithm and reducing file size over a minor increase in compression speed.

Compression Algorithms

DuckDB implements several lightweight compression algorithms, and we are in the process of adding more to the system. We will go over a few of these compression algorithms and how they work in the following sections.

Constant Encoding

Constant encoding is the most straightforward compression algorithm in DuckDB. Constant encoding is used when every single value in a column segment is the same value. In that case, we store only that single value. This encoding is visualized below.

When applicable, this encoding technique leads to tremendous space savings. While it might seem like this technique is rarely applicable – in practice it occurs relatively frequently. Columns might be filled with NULL values, or have values that rarely change (such as e.g., a year column in a stream of sensor data). Because of this compression algorithm, such columns take up almost no space in DuckDB.

Run-Length Encoding (RLE)

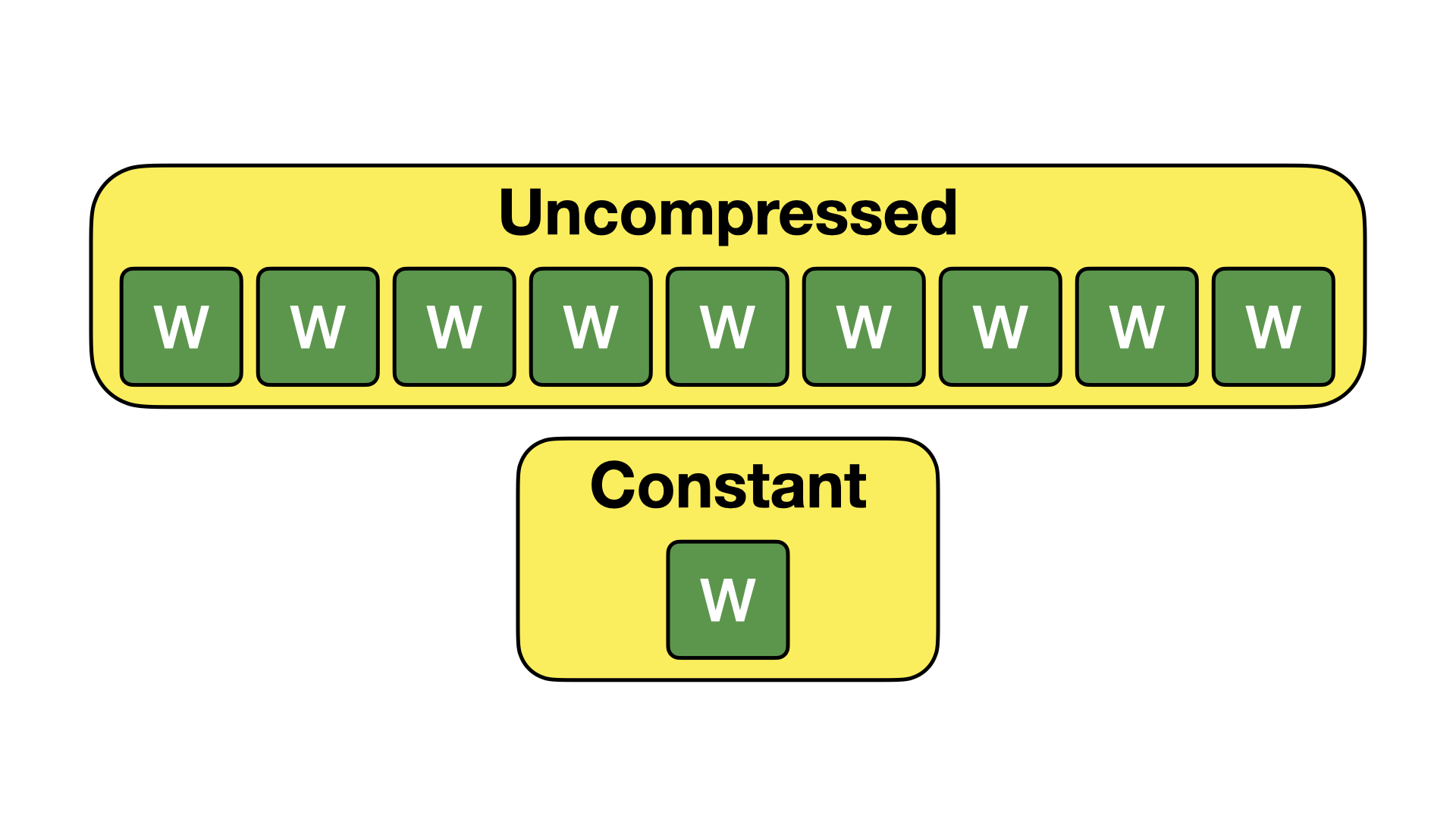

Run-length encoding (RLE) is a compression algorithm that takes advantage of repeated values in a dataset. Rather than storing individual values, the data set is decomposed into a pair of (value, count) tuples, where the count represents how often the value is repeated. This encoding is visualized below.

RLE is powerful when there are many repeating values in the data. This might occur when data is sorted or partitioned on a particular attribute. It is also useful for columns that have many missing (NULL) values.

Bit Packing

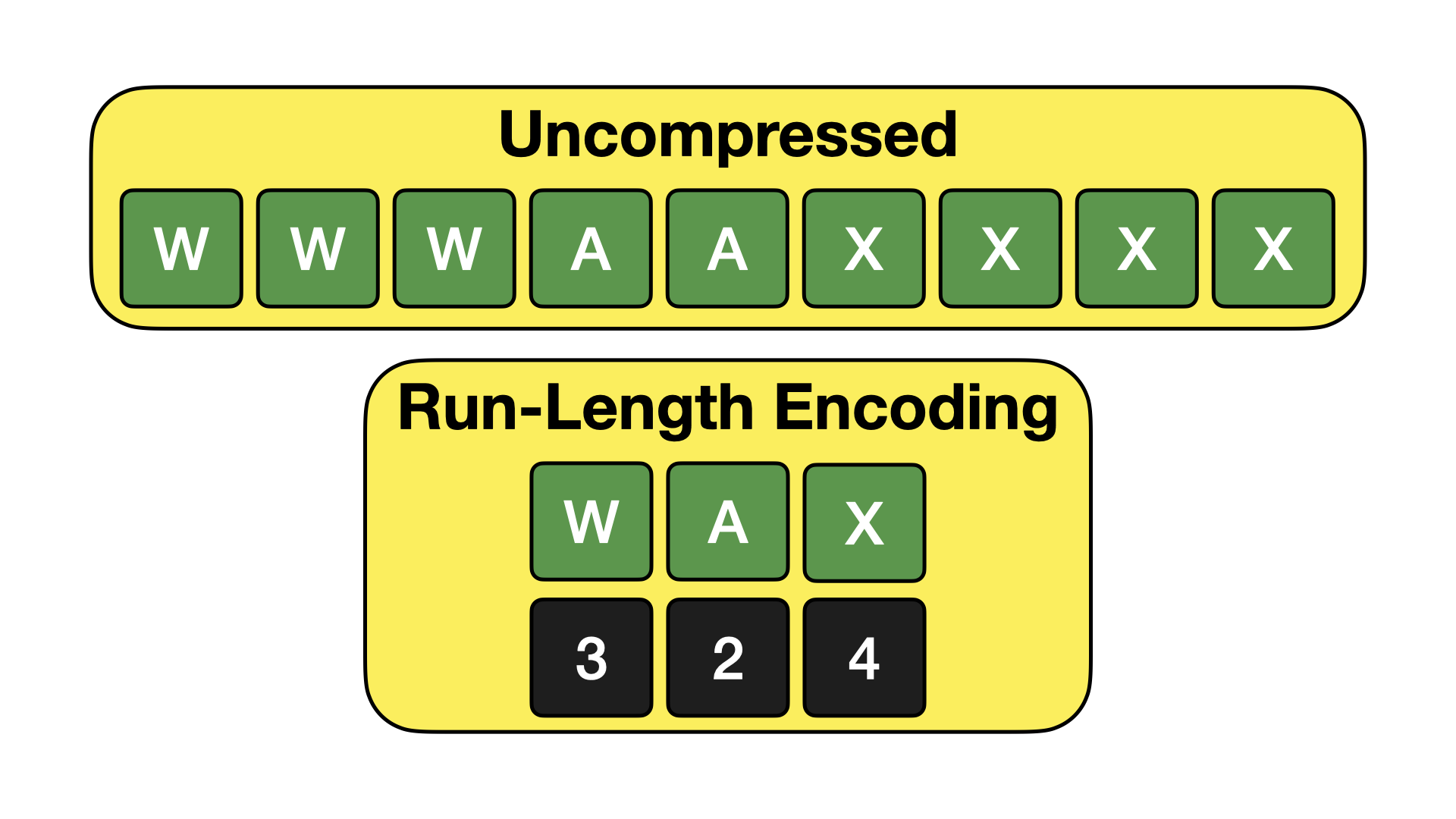

Bit Packing is a compression technique that takes advantage of the fact that integral values rarely span the full range of their data type. For example, four-byte integer values can store values from negative two billion to positive two billion. Frequently the full range of this data type is not used, and instead only small numbers are stored. Bit packing takes advantage of this by removing all of the unnecessary leading zeros when storing values. An example (in decimal) is provided below.

For bit packing compression, we keep track of the maximum value for every 1024 values. The maximum value determines the bit packing width, which is the number of bits necessary to store that value. For example, when storing a set of values with a maximum value of 32, the bit packing width is 5 bits, down from the 32 bits per value that would be required to store uncompressed four-byte integers.

Bit packing is very powerful in practice. It is also convenient to users – as due to this technique there are no storage size differences between using the various integer types. A BIGINT column will be stored in the exact same amount of space as an INTEGER column. That relieves the user from having to worry about which integer type to choose.

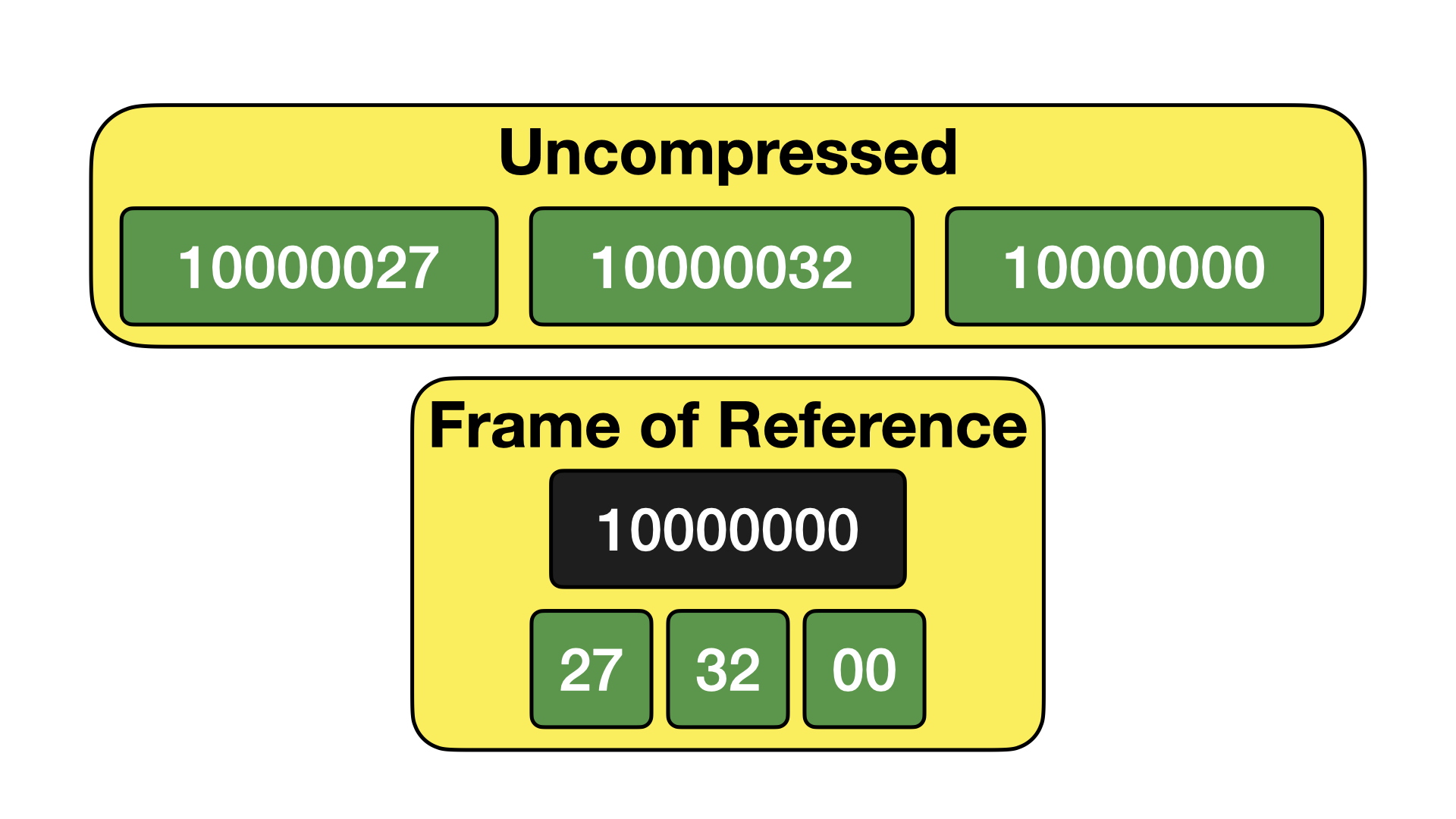

Frame of Reference

Frame of Reference encoding is an extension of bit packing, where we also include a frame. The frame is the minimum value found in the set of values. The values are stored as the offset from this frame. An example of this is given below.

While this might not seem particularly useful at a first glance, it is very powerful when storing dates and timestamps. That is because dates and timestamps are stored as Unix Timestamps in DuckDB, i.e., the offset since 1970-01-01 in either days (for dates) or microseconds (for timestamps). When we have a set of date or timestamp values, the absolute numbers might be very high, but the numbers are all very close together. By applying a frame before bit packing, we can often improve our compression ratio tremendously.

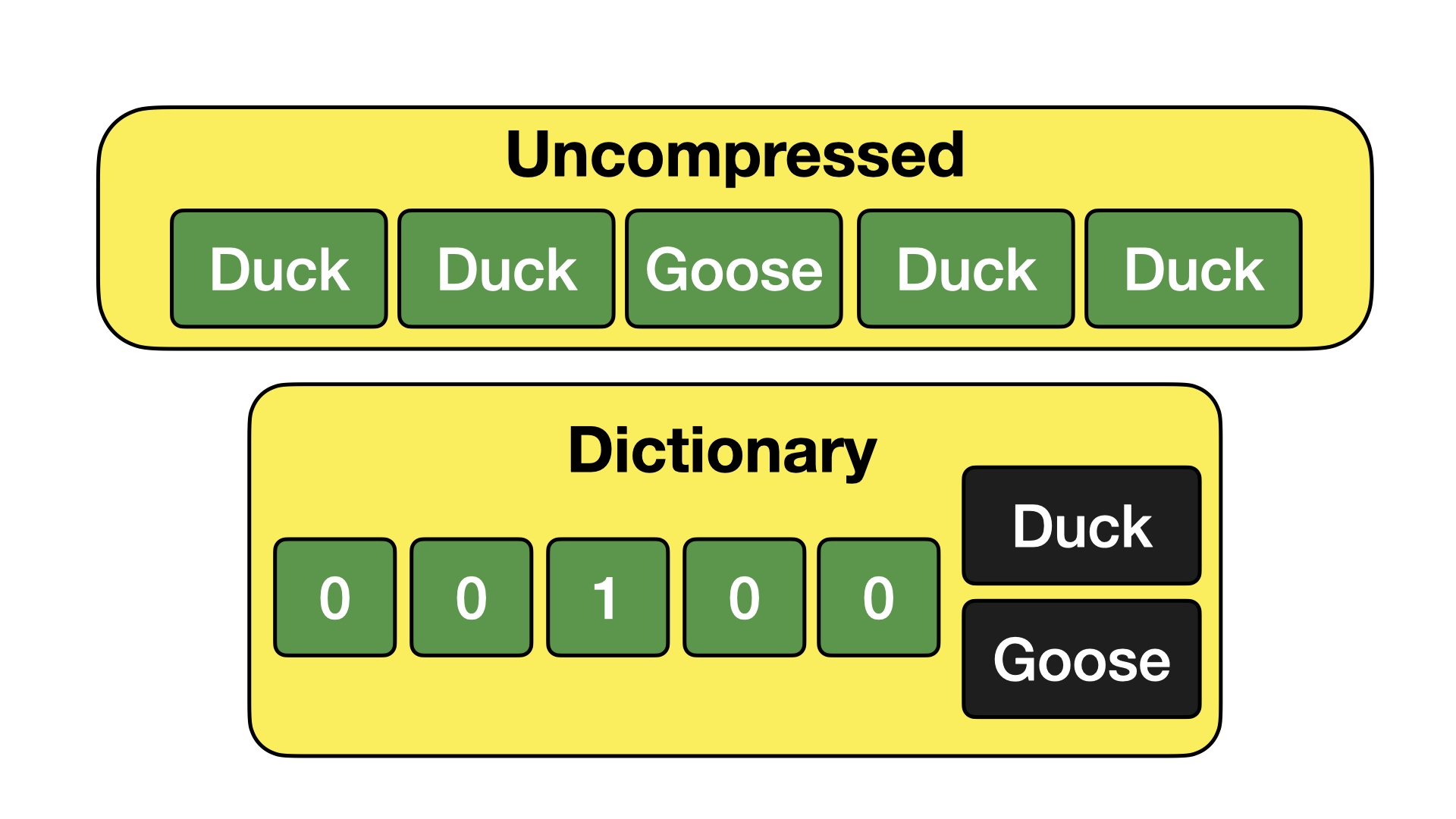

Dictionary Encoding

Dictionary encoding works by extracting common values into a separate dictionary, and then replacing the original values with references to said dictionary. An example is provided below.

Dictionary encoding is particularly efficient when storing text columns with many duplicate entries. The much larger text values can be replaced by small numbers, which can in turn be efficiently bit packed together.

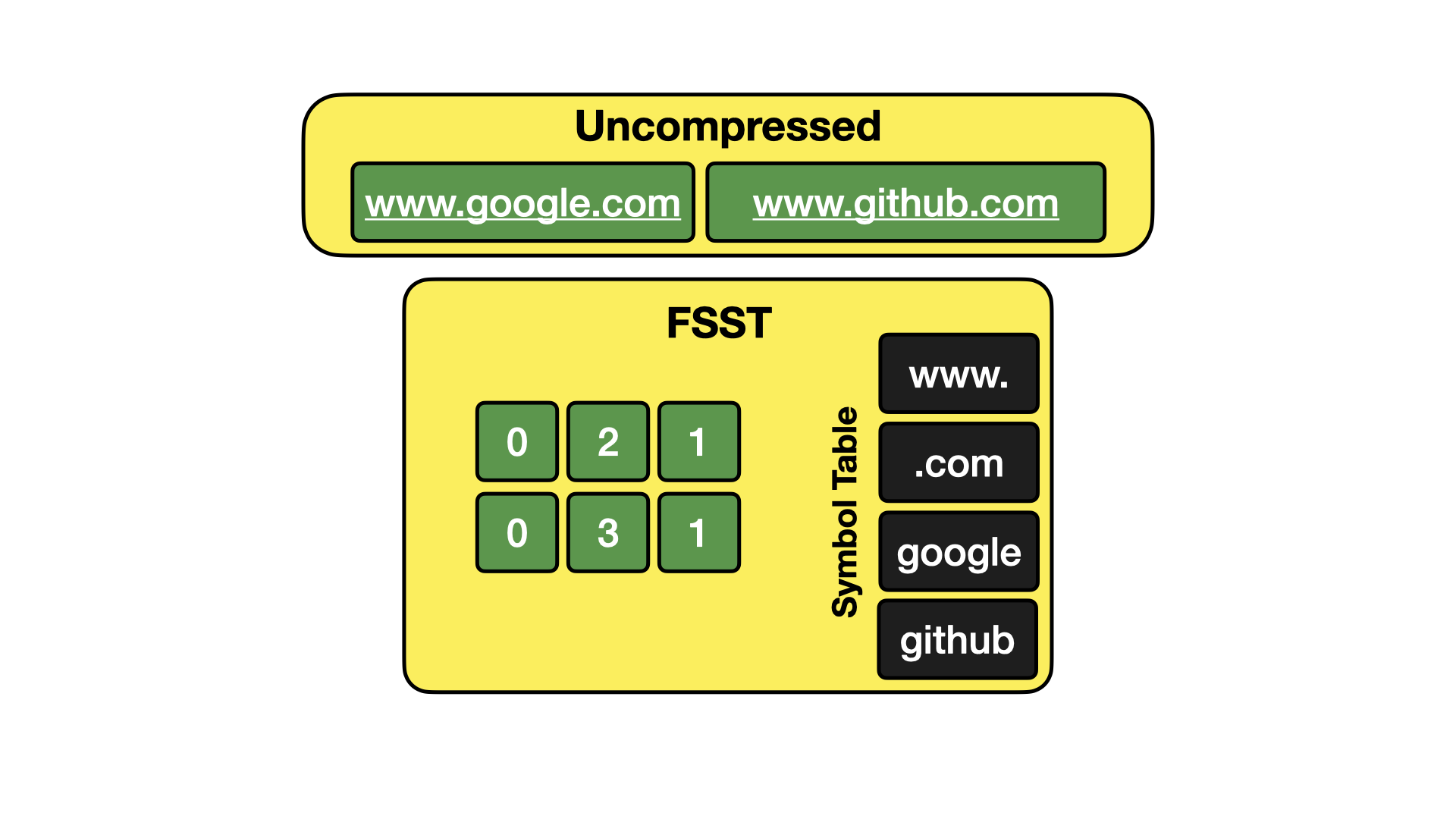

FSST

Fast Static Symbol Table compression is an extension to dictionary compression, that not only extracts repetitions of entire strings, but also extracts repetitions within strings. This is effective when storing strings that are themselves unique, but have a lot of repetition within the strings, such as URLs or e-mail addresses. An image illustrating how this works is shown below.

For those interested in learning more, watch the talk by Peter Boncz here.

Chimp & Patas

Chimp is a very new compression algorithm that is designed to compress floating point values. It is based on Gorilla compression. The core idea behind Gorilla and Chimp is that floating point values, when XOR'd together, seem to produce small values with many trailing and leading zeros. These algorithms then work on finding an efficient way of storing the trailing and leading zeros.

After implementing Chimp, we have been inspired and worked on implementing Patas, which uses many of the same ideas but optimizes further for higher decompression speed. Expect a future blog post explaining these in more detail soon!

Inspecting Compression

The PRAGMA storage_info can be used to inspect the storage layout of tables and columns. This can be used to inspect which compression algorithm has been chosen by DuckDB to compress specific columns of a table.

SELECT * EXCLUDE (column_path, segment_id, start, stats, persistent, block_id, block_offset, has_updates)

FROM pragma_storage_info('taxi')

USING SAMPLE 10 ROWS

ORDER BY row_group_id;

| row_group_id | column_name | column_id | segment_type | count | compression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | extra | 13 | FLOAT | 65536 | Chimp |

| 20 | tip_amount | 15 | FLOAT | 65536 | Chimp |

| 26 | pickup_latitude | 6 | VALIDITY | 65536 | Constant |

| 46 | tolls_amount | 16 | FLOAT | 65536 | RLE |

| 73 | store_and_fwd_flag | 8 | VALIDITY | 65536 | Uncompressed |

| 96 | total_amount | 17 | VALIDITY | 65536 | Constant |

| 111 | total_amount | 17 | VALIDITY | 65536 | Constant |

| 141 | pickup_at | 1 | TIMESTAMP | 52224 | BitPacking |

| 201 | pickup_longitude | 5 | VALIDITY | 65536 | Constant |

| 209 | passenger_count | 3 | TINYINT | 65536 | BitPacking |

Conclusion & Future Goals

Compression has been tremendously successful in DuckDB, and we have made great strides in reducing the storage requirements of the system. We are still actively working on extending compression within DuckDB, and are looking to improve the compression ratio of the system even further, both by improving our existing techniques and implementing several others. Our goal is to achieve compression on par with Parquet with Snappy, while using only lightweight specialized compression techniques that are very fast to operate on.